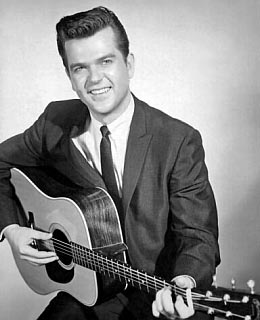

CONWAY TWITTY

Few music acts have successfully taken the leap from one genre to another. Building an audience, then pursuing a different fan base, can be a difficult transition given the loyalties so many people have to one style or another. But Conway Twitty pulled it off, even after being warned about the often-disastrous consequences. For him it was a matter of following the heart; his youthful fascination with rock and roll had transitioned into a hankering, in his thirties, to perform country and western music. The two genres shared some similarities, but crossing over to country meant he would have to develop an older fan base that, for the most part, scorned the musical tastes of rock-obsessed teens. Yet he achieved the unthinkable, achieving far greater success in the latter field.

As a child growing up in Friars Point, Mississippi near the banks of the Mississippi River, Harold Lloyd Jenkins (he was named after hazard-prone silent film star Harold Lloyd) was exposed to different types of music by simply walking across the street, or past a church, or riding a riverboat; from his perspective, blues, jazz, gospel, pop and country had a natural coexistence. Bluesmen performed in clubs down the street from the boarding house he lived in with his grandmother and on Saturday nights he would tune the radio to the Grand Ole Opry, broadcast from the seemingly-distant Nashville. Sundays he was intrigued by the singing he heard in church. Living next door to a black man he called "Uncle Fred," he learned the basics of blues guitar and harmonica. By the age of five or six, music was flowing in his bloodstream.

Around 1943, when he was ten, his family moved to Helena, Arkansas, about 70 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee on the other side of the river. He began pestering the owners of KFFA, a fairly new radio station (established about two years earlier) that regularly featured live performances by local acts. One such band, The Arkansas Cotton Choppers, invited Harold to sing on one of their shows. John Hughey, a kid he knew from school, heard the show and, having the same musical interests, they began practicing together each afternoon. John gravitated toward the steel guitar while Harold played rhythm guitar and harmonica; within a couple of years, with the addition of John's brother Gene Hughey and guitarist Wesley Pickett, they were calling themselves The Phillips County Ramblers and were given their own Saturday morning show on KFFA. In 1946, a Leon Payne song, "Cry Baby Heart," was recorded during a broadcast, the earliest documented audio of Harold's singing.

He played baseball in high school and was later offered an opportunity to enter the Philadelphia Philles' farm system...but then he was drafted. While stationed in Yokohama, Japan in 1954 and '55 he put together a band, The Cimarrons, and competed in an Army talent show. The first place act got to make an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show; as fate would have it, Harold's group came in second. During this time, John Hughey was back at home, supporting himself in the Memphis area as steel guitarist with local country band Slim Rhodes and the Mother's Best Mountaineers. The Cimarrons performed in serviceman's clubs in Japan and other parts of Eastern Asia until Jenkins was discharged in March 1956...just about the time Elvis Presley's career was taking off with his milestone hit "Heartbreak Hotel." Like many others inspired by Presley's sound and stage presence, Harold became a diehard rock and roller.

After returning to Helena, he journeyed a few hundred miles north to Springfield, Missouri, where ABC-TV's Ozark Jubilee originated, landing a job playing guitar for regular vocalist Tabby West (born Phyllis Spain, she had previously recorded for the Coral and Decca labels). Shortly afterwards he formed a new band, naming them The House Rockers; they headed to Memphis to audition for Sam Phillips at Elvis's former label, Sun. Phillips was impressed by some of the songs Harold had written but not his singing. Sun artist Roy Orbison, coming off his hit single "Ooby Dooby," was less critical; he cranked out a hot version of "Rockhouse" for his next Sun single; it was Harold's first officially-released composition and only notable Sun Records credit.

Despite his failure to get anything going at Sun, there were other companies interested in him...or, for that matter, anyone who gave off an Elvis-like aura. But Phillips' rejection weighed heavily and Harold began rethinking his whole approach. He decided his name wasn't exactly an attention-grabber and started coming up with different combinations, figuring it should be unique, even if it sounded a little weird. While studying maps for ideas, he came up with Conway from a city in Arkansas and Twitty from a small town in Texas. When his parents first heard the new stage name, they were baffled; why he would he want to be known by such an awful name? Don Seat, a guy he'd known while in the Army, became his manager and got him signed to Mercury Records. Working out of Owen Bradley's Nashville studio, the results were strong. The newly-christened Conway Twitty was confident his first effort (a revised take on one of his original Sun demos, "Give Me Some Love") would be huge. But "I Need Your Lovin'" stalled near the bottom of the national charts.

After just one follow-up, Conway received a hard dose of reality: Mercury dropped him from the roster. He and the band crossed the Canadian border and performed for several months in Hamilton, Ontario (Ronnie Hawkins, who'd thus far experienced similar difficulties in getting established, showed up soon afterwards). While there, Conway co-wrote "It's Only Make Believe" with House Rockers drummer Jack Nance. MGM picked up his contract and in May 1958, he and the band headed straight to Bradley's to wax several tracks with backing singers The Jordanaires, best known for their work on many of Presley's hits. "I'll Try" was issued as the A side, but nothing happened with it...until radio DJs starting turning the single over and playing the ballad side with its ascending melody and lyrics: '...my only prayer will be...someday you'll care for me...but it's o-only make be-lieve!' The song took off and in November 1958 it was at the top of the pop charts. A month later, the feat was repeated in the U.K.; Twitty toured there at a time when few non-superstar U.S. acts did so.

Twitty's "growling" delivery on parts of "It's Only Make Believe" weren't intentional, having come more from habit, but the vocal sound soon became a trademark. A similar Twitty-Nance song, "The Story of My Love," reached the top 30 in February '59 as a third Mercury disc, "Double Talk Baby," failed to compete. "Hey Little Lucy! (Don'tcha Put No Lipstick On)," his first uptempo MGM offering, reached the lower rungs in May. Then he was back in the top 30 with a remake of the 1950 Nat "King" Cole smash "Mona Lisa," riding in behind a similar rendition by Sun singer Carl Mann. Both did well that summer with Mann's gaining the edge, while Twitty's result reversed the downward trend. The next single, an unlikely, fast-paced reworking of "Danny Boy" (which began as Irish folk song "Londonderry Air" more than a hundred years earlier) made an unexpected December 1959 landing in the top ten.

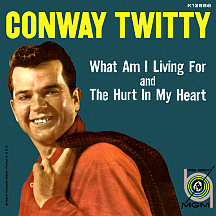

"Lonely Blue Boy" (written by frequent Presley contributors Ben Weisman and Fred Wise, it was first heard under the title "Danny," sung by Elvis in King Creole) ranks among Twitty's best performances, a growling, angst-ridden mid-tempo rocker that reached the top ten in February 1960 and was his second-best selling single while with MGM. The rhythm and blues influences of his youth showed up in "What Am I Living For," a cover of Chuck Willis's 1958 swan song that reached the top 30 that spring. Songwriter Dan Penn (who went on to write hits for Tommy Roe, James and Bobby Purify, The Box Tops and others) scored his first national hit with Conway's cool take on "Is a Blue Bird Blue," a top 40 entry in July. The next single was an R&B song composed by Willis that had been a hit in '54 for Ruth Brown: "What a Dream."

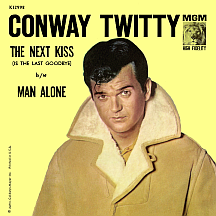

His place in pop culture had become obvious by this time. Peter Sellers parodied rock and roll on his LP Songs for Swingin' Sellers; Twit Conway was a fictional character ridiculed on the track "So Little Time." The 1960 Broadway musical Bye Bye Birdie quickly became a standing-room-only hit; guess who inspired its main character, Conrad Birdie? The comedic role was played by Dick Gautier (perhaps best known as Hymie, a robot detective on NBC-TV's Get Smart a few years later), who performed one of the show's songs, "One Last Kiss." An infectious Twitty tune, "The Next Kiss (Is the Last Goodbye)," was an answer of sorts to the film's satirically-growled song.

Conway entered the movie business in 1960, the result of a clause in his MGM contract (one of the main reasons Don Seat urged him to sign with the combination film studio/record label). Between May and August of 1960 he had non-singing roles in three comedies: Platinum High School (starring Mickey Rooney and Yvette Mimieux), College Confidential (alongside Steve Allen, Jayne Meadows and B-movie sex symbol Mamie Van Doren) and Sex Kittens Go to College (with Van Doren and Tuesday Weld). The films were shunned by critics, nor did they generate much revenue. Twitty's movie career ended within months of its start. More rocking remakes hit the charts: he put his own stamp on Jerry Lee Lewis's smash "Whole Lot of Shakin' Going On" (first recorded in '54 by Big Maybelle) and reached the pop top 40 for the eighth and final time in early '61 with "C'est Si Bon (It's So Good)," distinctly contrasting Eartha Kitt's vampish hit from '53.

The big screen version of Bye Bye Birdie became a major motion picture in 1963 with singer Jesse Pearson taking the role of Conrad Birdie. Touring was beginning to take its toll on Twitty by that time; he found the fanatical behavior of the teenage audience exhausting and questioned whether the rock star lifestyle was really what he wanted. Country selections were added to his shows; he had a preference for Harlan Howard's work. Howard attended one of his shows and suggested he do even more C&W material. This led to a session at a small studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Twitty put together an album's worth of the country songs he'd written. Harlan shopped these demos around and in early '63 one of them, "Walk Me to the Door," became a top ten country hit for Ray Price. Conway left MGM around that time and recorded a song he'd written for ABC-Paramount, "Go on and Cry," an R&B-style shouter unlike anything he'd previously done. After one other ABC single, the more easily identifiable "Such a Night" (debuted by Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters in 1954), he found himself without a label and at a crossroad.

After informing his manager and others close to him that he wanted to switch to country music, they adamantly disagreed, certain it would negatively impact his finances and likely end his career. But he had made up his mind. He began playing in small clubs for a fraction of what he'd been making off the big concerts of recent years. His career was clearly on a downward slide...until Harlan Howard took it upon himself to play some of those earlier country demos for Owen Bradley without telling him who he was listening to. Bradley's stable of Decca Records country stars (Webb Pierce, Kitty Wells, Loretta Lynn, Bill Anderson and the late Patsy Cline, among others) ranked among the biggest and best. Bradley, impressed that a "teen idol" could sound so credible as a country singer, showed interest and a meeting with Twitty was arranged. For his first Decca session, Bradley set him up with top Nashville musicians; Conway's previous steel guitarist and childhood friend John Hughey joined as well and remained with him on recordings and in concert for the next 20 years.

The first Decca single, Twitty original "Together Forever," drenched in Hughey's steel guitar and squarely in the "Nashville Sound" zone of 1965, completely bombed. Liz Anderson's "Guess My Eyes Were Bigger Than My Heart," Howard and Don Bowman's "Look Into My Teardrops" and several by Conway's wife Temple Medley (using her pen name, Mickey Jaco), including "I Don't Want to Be With Me," "Don't Put Your Hurt in My Heart," and "Funny (But I'm Not Laughing)," met with small amounts of airplay and lower-than-desired country chart placement. Despite the quality of those early efforts, country DJs didn't immediately buy into the notion of a former rocker daring to make an attempt at country music. But Conway was satisfied with any level of acceptance; he still had a career!

Nearly three years after signing with Decca, he suddenly soared to the top ten with Wayne Kemp's "The Image of Me," followed by the Kemp-Curtis Wayne-penned ballad "Next in Line," his first number one country single. Major hits followed, many employing themes of heartbreak, liquor, cheating and divorce set to the ever-present steel guitar. With three country chart-toppers by the end of the '60s, he scored his biggest yet in the spring of 1970; "Hello Darlin'," a song he'd written ten years earlier, is arguably his most famous recording. Its intro became the opening for his concerts; a dark stage, the softly-spoken words "Hello, Darlin'," followed by a lit stage and an audience willingly held captive by a singer in his prime throughout the late '60s, '70s and '80s. A whole new type of "obsessed" female fan emerged, a little older and enthralled by the increasingly sensual content of many of his songs.

In 1971 he duetted on the first in a series of hits with "Blue Kentucky Girl" Loretta Lynn; the superstar team won a Grammy award for "After the Fire is Gone" in the category Best Country Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group. Between the CMAs, ACMs and Grammys he received more than two dozen nominations during the '70s, '80s and '90s, winning three awards total, one from each association...or academy, as the case may be. In the mid-1970s his daughter, Joni Lee Ryles (she was the wife of singer John Wesley Ryles), an MCA artist under the name Joni Lee, sang on many of his recordings.

With fame and record sales came considerable wealth; he had a home built at a cost of more than three million dollars, called it Twitty City and opened it to the public in 1982 as a tourist attraction. Health problems came suddenly just nine years later; in 1993, at age 59, he died of a ruptured abdominal aneurysm, a heart-related issue. Twitty City was closed soon afterwards. Ultimately, Conway Twitty had a very long string of hits - 40 singles reached number one on the country charts between 1968 and 1986, a monumental achievement, more than anyone else at the time. All of that in addition to "It's Only Make Believe," the chart-topping number one pop hit that put him on the map in late '58.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- I Need Your Lovin' - 1957

- Maybe Baby - 1957

- It's Only Make Believe /

I'll Try - 1958 - Double Talk Baby - 1958

- The Story of My Love - 1959

- Hey Little Lucy! (Don'tcha Put No Lipstick On) /

When I'm Not With You - 1959 - Mona Lisa - 1959

- Danny Boy - 1959

- Lonely Blue Boy - 1960

- What Am I Living For - 1960

- Is a Blue Bird Blue /

She's Mine - 1960 - What a Dream - 1960

- Whole Lot of Shakin' Going On - 1960

- C'est Si Bon (It's So Good) - 1961

- The Next Kiss (Is the Last Goodbye) - 1961

- Sweet Sorrow - 1961

- Portrait of a Fool - 1962

- Go on and Cry - 1963

- Such a Night - 1964

- Together Forever - 1965

- Guess My Eyes Were Bigger Than My Heart - 1966

- Look Into My Teardrops - 1966

- I Don't Want to Be With Me - 1967

- Don't Put Your Hurt in My Heart - 1967

- Funny (But I'm Not Laughing) - 1967

- The Image of Me - 1968

- Next in Line - 1968

- Darling, You Know I Wouldn't Lie - 1969

- I Love You More Today - 1969

- To See My Angel Cry - 1969

- Hello Darlin' - 1970

- Fifteen Years Ago - 1970

- After the Fire is Gone - 1971

by Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn - You've Never Been This Far Before - 1973