PATSY CLINE

"Is she a country singer or a pop singer?" That's a question unlikely to have been asked about anyone prior to the 1950s; attempting a career in pop music just wasn't something western-style singers considered. But Patsy Cline had an exceptional gift, a voice that lent itself easily to pop-style ballads despite her preference for country. It wasn't her idea to gradually move away from fiddle and steel guitar accompaniment to stringed orchestras and elegant background vocalists but rather the people she worked with, some with an ear for what makes a star and at least one with a nose for the scent of greenbacks but a lack of foresight. What matters in the long run is that she recorded a little more than one hundred songs during her regrettably short, accident-prone life, and her entire output, regardless of genre or quality of material, is outstanding because of the sincere, emotionally flawless way she delivered a song.

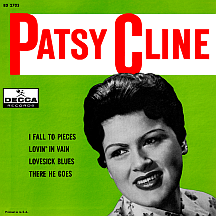

The climb wasn't easy by any means. Patsy's determination and talent found takers willing to open their doors to her. But a lot of effort was expended in getting a recording contract. Hard work finally resulted in a chart hit ("Walkin' After Midnight"), followed by a seemingly unstoppable decline that almost did her in. She was nearly back to square one before a second hit ("I Fall to Pieces") got things rolling again four years later. How many entertainers have had to go through the difficult process of establishing themselves...twice?

Virginia Patterson Hensley ("Ginny" to family and friends) was born in 1932 in the small town of Gore, Virginia, and wanted to be a performer practically out of the cradle. At age four she won an amateur dance contest held in Lexington, more than a hundred miles to the south. She studied piano in school and made such an issue of it that her parents relented and bought one around the time of her eighth birthday. They moved to nearby Winchester, Virginia, and in 1947 the 14-year-old Grand Ole Opry fan set her sights on the nearest thing the city had to America's leading country music radio songfest: a Saturday morning show on WINC hosted by local musician Joltin' Jim McCoy. Her plan was to show up unannounced and sing for McCoy and it took just two visits for her to get his attention; he was impressed and hired her on the spot.

In the early '50s, she began singing with Bill Peer and his C&W band The Melody Boys while beginning an on-again, off-again relationship with the bandleader. He suggested she change her stage name to Patsy (an abbreviation of her middle name). In March of '53 she married Gerald Cline and her marquee moniker was set in stone. An audition for the Grand Ole Opry didn't work out, but she managed to secure a regular spot on Ernest Tubb's radio show Midnight Jamboree on Nashville's WSM, broadcast live each Saturday night from Tubb's record shop, down the street and around the corner from the Ryman Auditorium where the Opry, which immediately preceded it, went out over America's airwaves. Town and Country Time, hosted by personality Connie B. Gay on Arlington, Virginia's WARL, was her next stop on the way to reaching a larger audience; Patsy's summer '54 performances of the Webb Pierce hit "I'm Walking the Dog" and Kitty Wells' signature song "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels" were taped during the show and sent out on transcription discs for other stations to air. These were essentially her first recordings..

Bill McCall, the owner of 4 Star Music Sales, a publishing company and record label based in Pasadena, California, was the first person to show tangible interest in Patsy. She signed a contract with the company in September despite one stipulation: McCall had final approval on everything she recorded. Rather than release her output on 4 Star, he had a licensing agreement with Coral Records, a division of Decca; A&R man Paul Cohen was impressed with her vocal ability, recognizing potential for success as both a country and pop act. Cohen had taken note of Patti Page's multi-million-selling "Tennessee Waltz" and other similar crossover triumphs. In his opinion, Patsy had a sound closer to mainstream Patti than twangy Kitty. McCall, on the other hand, was driven strictly by monetary concerns; what the records sounded like were of little importance. Recognizing her exceptional talent, he selfishly figured on making a great deal of money selling her versions of songs he owned.

The contract between 4 Star and Decca prevented Cohen from choosing material, yet allowed him to use any producers, arrangers and musicians he pleased. He tapped Owen Bradley for the assignment; with two decades in the business under his belt, the 39-year-old Bradley had led bands, played piano on hit records and worked in radio at WSM before joining Decca in the late '40s as a staff producer and songwriter. As Patsy was getting established, he was setting up Bradley Film and Recording Studios in a converted house in south Nashville and putting the finishing touches on a large Quonset hut behind it that eventually became known as "Bradley's Barn," the Nashville hot spot for recording music. Cline's efforts were done in the house and released on Coral in 1955 and '56. "A Church, A Courtroom, Then Goodbye," a sorrowful ballad of divorce by 4 Star writers Eddie Miller and W. S. Stevenson, wasn't the sort of thing Patsy would have chosen as her debut hunk of vinyl if she'd had any say in the matter; midtempo flip side "Honky Tonk Merry Go Round," penned by little-known songwriters Frank Simon and Stan Gardner, was closer to her preference. Neither side was particularly well received.

Follow-up "Hidin' Out," another slow Miller-Stevenson number, left Mrs. Cline cold. The third single had more energy; Miller's "I Love You, Honey" presented Patsy as a mid-century "Material Girl," while Virgil "Pappy" Stewart's "Come on In" came off as a feelgood invitation to '...make yourself at home.' Cohen moved her to Decca after this, figuring the larger-label affiliation might help set her on a hitmaking track. Radio and television appearances continued to be restricted to Virginia and the Washington, D.C. area. Initial Decca effort "Stop, Look and Listen," the jumpin'est track yet, failed to make headway.

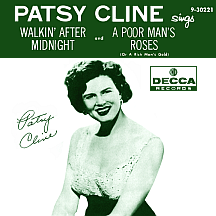

Her affair with Peer and overlapping marriage to Cline had run their course when Patsy met Charlie Dick and was soon engaged to be married a second time. Songwriting newcomers Don Hecht and Alan Bloch submitted a pop song - or was it a blues song? - called "Walkin' After Midnight," which they had earmarked for Kay Starr. McCall passed it to Patsy, who felt it wasn't country enough. Still, she recorded the song in late 1956 and performed it on Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts in January '57. Her initial instinct was proven wrong; response was immediate, Godfrey asked her back for many more appearances on his show, and Decca issued it with a Bob Hilliard-Milton DeLugg flip, "A Poor Man's Roses (Or a Rich Man's Gold)" (which Patti Page quickly covered for the pop market). "Midnight" was expertly delivered by Patsy, sounding much more mature than you'd expect from a 24-year-old (she hadn't been a typical teenager, either), touching on the best elements of country (an attention-grabbing steel guitar intro), pop and blues. It was a top ten country hit in March and reached the pop top 20 as Page's "Poor" cover enjoyed similar results.

Bradley, by this time handling production chores in the Quonset hut, gingerly moved Patsy in a pop direction; McCall didn't voice any objections (whatever it took to sell records!). Don Reid's "Today, Tomorrow and Forever" was arranged with a mild rock and roll feel. Pure pop act The Anita Kerr Singers began showing up on backing vocals ("Three Cigarettes in an Ashtray," "Stop the World (And Let Me Off)"), but nothing seemed to work (not for Patsy, anyway; "Stop the World," written by Stevenson and country singer Carl Belew, was a hit in early '58 for Johnnie and Jack). Momentum was further interrupted when she became pregnant and took several months off.

In 1958 and '59 her career seemed to be moving backwards. But as the small roadside clubs beckoned and it appeared she might not be making records much longer, she achieved a goal she'd dreamed of since childhood: the Grand Ole Opry made her a regular in January 1960. The high profile exposure on the nation's most listened-to country music radio show offered encouragement. One other important thing happened in 1960: her contract with Bill McCall and 4 Star came to an end. She was free to sign with any company; RCA Victor showed interest, but she chose to stay with Decca and that was fine by Owen Bradley. The explosive breakthrough of the label's 15-year-old dynamo Brenda Lee in the early months of the year supported his belief (based in part on the direction Chet Atkins was moving in with his country roster at RCA) that the pop field (and even rock and roll, for that matter) was where the major stars were being made. Free from McCall's restrictions, he set about the task of taking Patsy to the next level. Female singers still hadn't been widely accepted in country music. A select few stood out among the boys' club of the '50s. Jean Shepard and designated C&W queen Kitty Wells managed to carve out careers while the few other women who made a mark, Patsy Cline included, had done so in a one-hit way. Until that pattern shifted, it made sense to commit to a new approach.

Songwriter Harlan Howard had burst onto the scene in 1958 with "Pick Me Up on Your Way Down," a number two C&W hit for Charlie Walker, scoring even bigger the following year with "Heartaches by the Number" (Ray Price had the country hit and Guy Mitchell topped the Hot 100); singer-songwriter Hank Cochran hadn't yet made his mark. Together they composed "I Fall to Pieces," an oddly-titled lost-love tune that, like much of the material offered to Patsy, didn't thrill her at first. Nevertheless, the song was recorded in Bradley's Barn in November 1960 with backing by Elvis regulars The Jordanaires. The single got off to an extremely slow start in early '61, but promotional reps kept working it, picking up adds at radio stations here and there. In April the song debuted on the country charts; in May it worked its way onto the pop charts.

Disaster struck. In June, Patsy and her brother, Sam Hensley, were in a head-on car crash; she went through the windshield and spent more than a month in the hospital. In late July she appeared (but didn't perform) at the Grand Ole Opry...in a wheelchair. Meanwhile, "I Fall to Pieces" continued its persistent upward trajectory, hitting number one country and top 20 pop in August. Second breakthrough finally realized, four years after the first. She had no further resistance to pop ballads after that. The next hit came courtesy of Willie Nelson, who'd been gaining momentum as a songwriter; "Hello Walls" was a huge hit for Faron Young in the spring and "Funny How Time Slips Away" made its mark late in the year in versions by Billy Walker (country) and Jimmy Elledge (pop). "Crazy" could have been definitively rendered by a male singer (Willie later did it himself), but it was Patsy's recording that made a lasting impact; it became her only top ten hit on the Hot 100 in December 1961 and remains the version by which all others are judged.

The lyrics of "She's Got You" oozed regret ('I've got your memory, or has it got me?'); Hank Cochran's solo contribution to her string of hits connected with a rapidly-expanding fan base. A top 20 pop hit in March 1962, it spent most of April and May at number one on the country charts. Bradley arranged Harlan Howard's "When I Get Through With You" like a teen-pop tune; it was backed by the more adult-skewing "Imagine That," a Justin Tubb composition. Sad songs had become her forte; Carl Perkins contributed "So Wrong" and Patsy's rendition of "Heartaches" wrung emotion out of lyrics initally passed over in the famous Ted Weems/Elmo Tanner whistling version of the 1930s.

"Leavin' on Your Mind," penned by successful tunesmith and singer Wayne Walker, was nearing the country top ten on March 5, 1963, when a small Piper Comanche airplane piloted by Patsy's manager, Randy Hughes, who'd been licensed to fly the previous summer, took off from Dyersburg, Tennessee around 6PM, on its way to Nashville after completing a concert tour. A witness saw the plane go down near Camden at approximately 7PM. The bodies of Hughes and touring artists Patsy Cline, Cowboy Copas (Hughes's father-in-law) and Hawkshaw Hawkins (Shepard's husband) were found the following morning after an all-night search. Adding to the tragedy, Jack Anglin of Johnnie and Jack (who'd eclipsed Cline's version of "Stop the World (And Let Me Off)" five years earlier) died in an auto accident en route to a memorial service for Patsy that was held in Nashville three days later.

Patsy's remake of Don Gibson's "Sweet Dreams (Of You)," a hit for both Faron Young (in '56) and Gibson (in '56 and '60) was a hit shortly afterwards and has been closely associated with the singer ever since (Sweet Dreams was the title of the 1985 biopic starring Jessica Lange). The notion that Patsy's premature death is partly responsible for the reverence millions of modern day fans have for her is not entirely off-base. Perhaps her greatness, which ultimately overhadowed her lifelong struggle, would have faded had she lived to see the 21st century. By leaving us so abruptly at the age of 30, she agelessly retains the image she possessed at her peak. Patsy Cline's wonderful recordings, as a result, are that much more fascinating...otherworldly, even.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- A Church, a Courtroom, Then Goodbye /

Honky Tonk Merry Go Round - 1955 - Hidin' Out - 1955

- I Love You, Honey /

Come on In - 1956 - Stop, Look and Listen - 1956

- Walkin' After Midnight /

A Poor Man's Roses (Or a Rich Man's Gold) - 1957 - Today, Tomorrow and Forever - 1957

- Three Cigarettes in an Ashtray - 1957

- Stop the World (And Let Me Off) - 1958

- If I Could See the World (Through the Eyes of a Child) - 1958

- Gotta Lot of Rhythm in My Soul - 1959

- I Fall to Pieces - 1961

- Crazy /

Who Can I Count On - 1961 - She's Got You /

Strange - 1962 - Imagine That /

When I Get Through With You (You'll Love Me Too) - 1962 - So Wrong /

You're Stronger Than Me - 1962 - Heartaches /

Why Can't He Be You - 1962 - Leavin' on Your Mind - 1963

- Sweet Dreams (Of You) /

Back in Baby's Arms - 1963 - Faded Love - 1963

- When You Need a Laugh - 1964

- Someday You'll Want Me to Want You - 1964

- He Called Me Baby - 1964