CHUCK WILLIS

From an early age, Chuck Willis was mainly interested in writing songs...and he was very good at it. When inspiration caught hold, he would lock himself away for days at a time working on new material, no collaborators needed. But before long this fascination with melody and lyrics took him to another level as he began singing, something it turned out he also had quite a knack for. His style wasn't overbearing nor was it too soft; he hit an even keel with an approach that worked well for fast and slow tempos. Several rock and roll classics resulted.

He lived in Atlanta, Georgia most of his life. Born Harold Willis in 1928, it was his fate to grow up near Decatur Street in the downtown area where a great many nightclubs provided a bustling backdrop of jazz and blues sounds. Ideas for songs came naturally and by 1946, when he was 18, he was performing at "Teenage Canteens" presented by the YMCA, working with seasoned bandleader Red McAllister (who later recorded for King Records) and another band led by trumpeter Roy Mays. After awhile he caught the eye of popular deejay Zenas "Daddy" Sears of WGST, who booked him into local venues on a regular basis. In 1951, with Chuck on the verge of signing a contract with Savoy Records, Sears got him an "in" with Danny Kessler, who'd been hired by Columbia to build a roster of black artists.

Willis had penned both sides of his first (and only) Columbia single. "Can't You See" and "It Ain't Right to Treat Me Wrong" were structured like many blues recordings of the day. Shortly afterwards, Columbia revived the Okeh label (which had been active off-and-on from the late 1910s to mid-'40s) and appointed Kessler head of A&R. Chuck Willis soon became its biggest artist. Early tracks, like "Loud Mouth Lucy," were more rocking than the songs that would gain him a large audience; Roy Mays (who'd by then recorded "Daddy Sears Jump" for the small Gerald label) backed him on several of these early recordings. Yet it was his softer-but-agonized performance of "My Story" ('Where is my baby?') that set the tone for future releases after it shot up the rhythm and blues charts in the fall of 1952. Soon he was hosting a Saturday night music series on an Atlanta TV station, a rarity for a black musician even on a local level.

Though supportive of his songwriting, Okeh decided to play another angle by having him cover Fats Domino's suicidal smash "Going to the River." With the original at number two in the spring of '53, Chuck's less-dire-sounding cover was right there in the top ten, offering a lyrical switch (Fats' 'When she left me I bowed my head and cried' became 'Every livin' body needs someone to call their own' in Chuck's hands). The public responded to this softer approach and he answered with two more R&B top tens, the pleading "Don't Deceive Me" in the summer of '53 and effectively mournful "You're Still My Baby" in early '54.

While traveling with Chuck on an all-star tour, Atlantic Records diva Ruth Brown, who'd keenly taken note of his songwriting prowess, asked him to write one for her. "Oh What a Dream" was that song, one of her biggest hits (an R&B number one in the summer of 1954) while a cover by Patti Page reached the pop top ten. His dream of writing songs for others was taking shape in a similar pattern; "Close Your Eyes" was a major hit for The Five Keys in the spring of 1955 (Peaches and Herb repeated the feat 12 years later), just as The Cardinals were scoring with "The Door is Still Open" (also a hit for Dean Martin after the passage of nine years). Right when Ruth was topping the charts, an uptempo, Latin-vibe original recorded by Chuck became perhaps his most famous song: "I Feel So Bad," his fifth R&B top ten, had a second life by way of a note-for-note remake by Elvis Presley that became a major hit in '61.

Later Okeh efforts struggled in comparison to his 1952-to-'54 output; "Lawdy Miss Mary," a scorching track, saw some regional action in early '55 and he joined The Sandmen (who'd just backed Brook Benton on his very first single) for "I Can Tell." Quincy Jones was involved with Okeh at that time and led the orchestra on Chuck's 1955 recording of "Search My Heart," but it failed as a potential remedy for more a year of lackluster sales. Danny Kessler was Chuck's manager by this time; Zenas Sears had moved on, keeping busy with WAOK (AM 1380), an Atlanta station he'd purchased with business partners and turned into a successful blues and R&B-formatted music station. When Chuck's contract with Okeh expired, he signed with Atlantic. Label founder Herb Abramson put him together with arranger Jesse Stone (who'd built a long track record writing, producing and arranging hits for the company over its entire nine-year history). The promise of Willis's strong Okeh output was improved threefold during his time with Atlantic.

Stone was a creative marvel, always thinking "out of the box" where music production was concerned; wind chimes were employed as a subtle backing to "It's Too Late," a ballad otherwise very much along the lines of Chuck's earlier works. Suddenly he found himself back in the R&B top ten, after a two-year absence, in the summer of 1956. Steel guitar, an instrument not often heard outside the country music realm, was used effectively on his great two-sided hit disc "Whatcha' Gonna Do When Your Baby Leaves You" and "Juanita." He continued to write songs for other acts like The Clovers, Lula Reed and The Cadillacs ("Let Me Explain," the flip side of the group's big hit "Speedoo"). Chuck's guitar-playing cousin Robert Willis began making records in the mid-'50s for Ebb ("Never Let Me Go") and other labels. Later calling himself Chick Willis, he did a couple of duets in 1962 with the dynamic-but-hitless soul diva Chyvonne Scott. Chick settled into a hybrid blues-soul groove and made a number of mildly suggestive recordings (the best-known a 1972 single called "Stoop Down Baby").

The pinnacle of Chuck Willis's career came in the spring of 1957 with a remake of Georgian Ma Rainey's 1924 Paramount Records classic, "See See Rider Blues," made popular again when Harlem star Bea Booze made it a bit more sexy in 1943 on the Decca label. Chuck's rock variation, "C.C. Rider," had a distinct vibraphone intro, backing singers and a catchy sax riff by Gene "Daddy G" Barge (later a key player on Gary (U.S.) Bonds' string of hits). During a spring and summer run it nearly went top ten on the pop charts while climbing to number three in R&B sales and number one in disc jockey play.

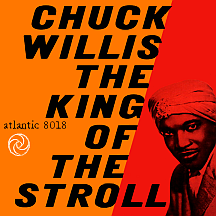

Daddy G joined Chuck's band in '57 and was also featured on "Betty and Dupree," a song based on the true story of 1920s thief and murderer Frank DuPre of Atlanta and his allegedly corrupt girlfriend Betty Andrews. Several songs about the ill-fated lovers had appeared in various forms for more than 30 years; Willis performed his lyrically nonspecific version on the February 15, 1958 premiere of The Dick Clark Show on ABC-TV (shortly afterwards it was retitled The Dick Clark Beech-Nut Show when Beech-Nut gum signed on to sponsor the Saturday night series). "The Stroll," instigated by The Diamonds, was the dance craze of the moment and the beat of Chuck's track fit the dance perfectly. Dick dubbed him "The King of the Stroll" and the name stuck; Atlantic issued an album using this title with "Betty and Dupree" as the lead track. Chuck's career was kicking into high gear...less than two months before his death.

The late-20-something Willis was self-conscious about losing his hair, which had thinned to the point that he started wearing turbans, covering what he considered a defect while giving him a different image, though not a new one: saxophonist Lynn Hope had used it as a tradmark a few years earlier, while Screamin' Jay Hawkins (that "I Put a Spell on You" wild man), a friend of Chuck's, frequently sported one and suggested he give it a try. Someone came up with another nickname, "The Sheik of Shake"...but the hit singles and crazy names were for naught. Chuck had suffered with ulcers for years but didn't realize his condition had reached serious proportions; it didn't help that he drank a lot. On April 10, 1958, he died of peritonitis, a serious infection of the abdomen.

As an artist, Willis had really hit his stride in '57 and '58, which only made the tragedy of a person losing his life at age 30 all the more devastating. Many felt both sides of his next single poignantly, though randomly, foreshadowed his death. The plaintive "What Am I Living For" and livelier "Hang Up My Rock and Roll Shoes" had titles prone to misinterpretation; neither song's lyrics was particularly downbeat, the first being about romantic longing and the second a protest against his mother's dislike of the current music. Austrian Fred Jay and Philly-born pianist Art Harris had written the former, a top ten hit shortly after Chuck's passing. Throughout his all-too-brief career, the soft-spoken singer composed nearly every song he recorded and provided numerous others with hit-worthy material. Oddly, his two biggest hits were songs he hadn't written.

A follow-up single, the optimistic "My Life," was taken from his initial 1956 Atlantic session. The next, "Keep A-Driving," came from the fateful session that had turned out the two-sided hit. In 1959, "Just One Kiss" was his final single. His many compositions have continued to be recorded by multi-genre artists who also consider themselves fans. His cousin Chick continued performing and making records well into the 21st century and was able, through various interviews, to give more insight on his famous cousin than Chuck himself had done. Some of his hits have become favorites among the rock community; for example, The Band recorded "Hang Up My Rock and Roll Shoes" in 1972, helping to make the title one of rock's most famous catchphrases. This is just one reason Chuck Willis has retained significance well beyond his unfortunate early demise.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Can't You See /

It Ain't Right to Treat Me Wrong - 1951 - Loud Mouth Lucy - 1952

- My Story - 1952

- Going to the River - 1953

- Don't Deceive Me /

I've Been Treated Wrong Too Long - 1953

by Chuck Willis and the Royals - You're Still My Baby - 1954

- I Feel So Bad - 1954

- Lawdy Miss Mary - 1954

- I Can Tell - 1955

by Chuck Willis and the Sandmen - It's Too Late - 1956

- Juanita /

Whatcha' Gonna Do When Your Baby Leaves You - 1956 - C.C. Rider - 1957

- That Train Has Gone - 1957

- Betty and Dupree - 1958

- What Am I Living For /

Hang Up My Rock and Roll Shoes - 1958 - My Life - 1958

- Keep A-Driving - 1958

- Just One Kiss - 1959