GENE VINCENT

AND HIS BLUE CAPS

The switch had been flipped. With the chart-topping achievement of "Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley and his Comets in the spring and summer of 1955, many male singers and groups with a feel for "the beat" emerged from all directions. Within months, the sneering, hip-shaking Elvis Presley set a precendent for slightly-dangerous rock idols who would make millions of parents with teenagers extremely nervous, fearful that their sons would imitate such hooligans or their daughters might, perish the thought, actively pursue them. Almost immediately after the rise of the "Pelvis," another rock and roller appeared, a little wilder, his recordings even more unruly than what Elvis, Scotty Moore and Bill Black had done to get Sam Phillips excited a couple of years earlier at the Sun Studio in Memphis. Virginia-born Vincent Eugene Craddock was ready to cause a few public disturbances!

Raised near the swamps outside Norfolk, he was a fan of country and gospel music and began practicing guitar around the age of 12. Drawn to a career in the military, he lied about his age and joined the Navy at age 16, just in time to serve at the height of the Korean conflict in the early '50s. When 18-year-old Gene saw Marlon Brando in the 1953 biker film The Wild One, he wanted to be a leather-jacketed ladykiller just like the guy he saw onscreen. Back home in Norfolk, while still serving in the Navy, he purchased a Triumph motorcycle but was in an accident not long afterwards that seriously injured his left leg; doctors suggested amputation, but Gene decided to take his chances with the pain and potential deformity. At the first opportunity, he resumed speeding around on his bike, accepting the dangers that can come with such a risky decision.

Still playing guitar, he and a Navy buddy, Donald Graves, wrote a few songs including "Be-Bop-A-Lula," its title inspired by a Little Lulu comic book. Country star Hank Snow's All-Star Jamboree made its way to Norfolk in May 1955 with Presley on the bill; after seeing the future "King" live and up-close, Gene figured he too could pull off a stage presence like that! WCMS radio, Norfolk's AM 1050, put out an advertisement for local talent and before long he was featured on some broadcasts. The station's manager, Bill "Sheriff Tex" Davis, offered to manage Vincent's career, swiftly buying the rights from Graves (on the cheap) for his share of the songwriting in order to give himself co-writing credit. What a coincidence! Elvis had Colonel Tom and Gene had Sheriff Tex and both had to deal with the consequences of forfeiting a large degree of control over their careers. Just like a lot of other guys.

Using the shorter stage name Gene Vincent, he put together a band made up of local musicians: "Galloping" Cliff Gallup on lead guitar, "Wee" Willie Williams on rhythm guitar, "Jumpin'" Jack Neal on bass and "Be-Bop" Dickie Harrell on drums, calling them The Blue Caps after President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who famously wore a blue cap whenever he was on the golf course. Could it have occurred to Gene to use the nickname "Lefty"? His leg-limp was ever-present during shows and became a trademark of sorts. It was a problem that was only going to get worse throughout his life.

As Elvis's "Heartbreak Hotel" reached the top of the charts in the spring of '56, record labels began frantically searching for Presley successors. Tex was able to get an audition for Gene with Ken Nelson, an A&R man and producer for Capitol Records. He was signed immediately and recorded his debut single in Nashville in May. "Be-Bop-A-Lula" ('...she-e-e's my baby now, my baby now, my baby now...') was backed with "Woman Love," a steamy midtempo tune penned by country pro Jack Rhodes and Capitol staffer Dick Reynolds that caused a minor controversy (Gene's pronounciation of the word 'huggin,' to some ears, sounded like it started with an 'f') and the "depraved" track was instantly banned by quite a few radio stations. But the A side prevailed (and I 'don't mean maybe'); it reached the top ten in July, hitting its peak at number seven the same week Presley's "I Want You, I Need You, I Love You" became his second number one hit. Many listeners mistook Vincent for the chart-topping star; even Elvis's mother, Gladys Presley, was fooled when she first heard it!

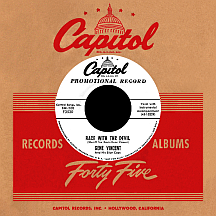

Follow-up "Race With the Devil" (another song penned with Graves that gave credit to Davis) is a fast-paced rocker, its satanic protagonist ('...here come the devil doin' a hundred 'n' one!') suggesting some drivers were reckless and/or evil. The subject matter may have been a little too bold; the single stalled in the lower ten of the Top 100. The record was more successful in the U.K., hinting at what the future held. Flip side "Gonna Back Up Baby," written by unsung rocker Danny Wolfe, was an A-side-worthy scorcher in its own right. Gene mounted a series of successful, often extended, tours with his rough-and-tumble Blue Cappers. As with Elvis and other rock and rollers, parents disapproved en masse while youthful concertgoers loved the unrestrained fun of it all. After a stretch, Gallup and Williams cracked under the pressure of the constant traveling and quit the band (though Gallopin' Cliff continued contributing to Gene's studio sessions). North Carolinans Russell Williford (lead guitar) and Paul Peek (rhythm guitar) took their places and the rock kept rollin'. Fall release "Bluejean Bop" (and its uproarious flip "Who Slapped John") was another strong two-sider that again, frustratingly, fared better in England.

Gene and the Blue Caps made their movie debut near the end of the year in 20th Century-Fox's color extravaganza The Girl Can't Help It (Little Richard sang the famous theme) starring Tom Ewell and designated "sexpot" Jayne Mansfield; a lip-synced "Be-Bop-A-Lula" is the highest-resolution clip available of the band in action. More strong, but non-hit, efforts followed: Jerry Reed's "Crazy Legs," about a boppin' dance queen, and the splendidly nonsensical "B-I-Bickey-Bi, Bo-Bo-Go." Then in the summer of '57 there were two more defections: bassist Neal and their manager, Sheriff Tex! Ed McLemore, who also represented Sonny James and Buddy Knox, took his place. Drummer Dickie recommended a friend from Norfolk, Tommy Facenda, who functioned strictly as a backing vocalist (he and Paul were often seen singing and clapping onstage to Gene's left and right). Other band members came and went, including guitarist Johnny Meeks, bass player Bobby Jones and pianist Max Lipscombe (who went by the name Scotty McKay). They began recording at the main headquarters, the Capitol Tower in Hollywood, California; soon-to-be country sensation Buck Owens played guitar on some of the sessions.

Songwriter Bernice Bedwell (who also wrote songs for rocker Bobby Summers) made her best mark in the biz with "Lotta Lovin'," which kept Gene in the top 20 from September to November; its flip, "Wear My Ring," an early effort by Bobby Darin and Don Kirshner, received significant airplay as well. The third "bop" drop came late in the year: "Dance to the Bop" was a solid top 50 seller. This welcome return to hit territory extended Gene's tenure at Capitol. He joined a tour of Australia ("The Big Show") with Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, female rocker Alis Lesley and soon-to-be Down Under star Johnny O'Keefe, whose band backed everyone but Richard (the flamboyant star, by the way, "found religion" - again - and quit in the middle of the tour).

1958 singles included "I Got a Baby," "Rocky Road Blues" and "Baby Blue," which (along with "Dance in the Street" and hit 45 "Dance to the Bop") were performed in the black and white teen-culture flick Hot Rod Gang, an independent and much-lower-budget production than the first movie, though this one has become a cult favorite, partly due to Vincent's extended screen time. Two great singles appeared in late '58: a doo wopper, "Git It," and "Say Mama" ('...can I go out tonight?'). About this time, crack saxophonists Jackie Kelso and Plas Johnson joined Gene on some of his studio recordings.

There were still more changes in the Blue Caps lineup. Tommy Facenda left to take a shot at solo stardom, had one single on the Nashville-based Nasco label, then headed back to Norfolk to record for Frank Guida's Legrand label, which resulted in the infamous "High School U.S.A.," issued on Atlantic Records in 28 regional versions, the combined lot placing Tommy in the top 40 during the fourth quarter of '59. His "Clapper Boy" pal Paul Peek left Vincent's group next, going on to make records for NRC, Fairlane, Mercury and Columbia. Two made the national charts: "Brother-In-Law (He's a Moocher)" (an answer to Ernie K-Doe's "Mother-In-Law") in 1961 and "Pin the Tail on the Donkey" in '66.

In early 1960, Gene received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the 1700 block of Vine Street in front of the Hollywood Palace; not many rock and rollers of his era were honored in this way. From that point on, he was nearly invisible in the United States as Europe became his regular stomping grounds. "Wild Cat," bearing the first of many solo credits, was a hit in the U.K. and there were more to come, though an unfortunate tragedy nearly did him in. In April 1960, while traveling in a cab from a show in Bristol to the London airport with Eddie Cochran and Eddie's girlfriend, songwriter Sharon Sheeley, the driver ran into a cement post at high speed. Gene and Sharon were injured...and Eddie was killed. The problems with his bum leg complicated matters; while he recuperated, "My Heart" became a top 20 U.K. hit. Three more Brit hits followed in '60 and '61: "Pistol Packin' Mama," "She She Little Sheila" and "I'm Going Home."

So he moved to England...why not? With his popularity going great guns, he decided to buy a house in London. For the next few years, tours of the U.K., France and several other European countries became routine. In April 1962, he crossed paths with The Beatles at the Star Club in Hamburg, Germany, then again in July at the Cavern Club in Liverpool where they were his opening act (still prior to scoring their first hit). Gene appeared in another movie that year (It's Trad, Dad!), but was finally dropped from the roster of Capitol Records in 1963. He returned to the U.S. a couple of years later and had three singles on the Challenge label in 1966 and '67. The influence of British blues is evident on "Bird-Doggin'" (penned by Keith Colley), while "Lonely Street" (a remake of Andy Williams' 1959 hit) found him in a more introspective mood. On "Born to Be a Rolling Stone," an original co-written by Joe E. Johnson, his sound is unrecognizable to any but the most diehard fan.

Further operations on his leg sidelined him for long periods, but he made a return in 1969, working with producer Kim Fowley, mostly on remakes of some of his favorite oldies for the Dandelion label, one of which was his own "Be-Bop-A-Lula '69." His final shot came with two albums for Kama Sutra Records in 1971; "Sunshine" (penned by Mickey Newbury) reveals an exceptional adaptability to a softer rock style. A sad song, "The Day the World Turned Blue," was the final single released during his lifetime.

Later failures and increasing physical pain led to depression and heavy drinking. Gene died on October 12, 1971 at the age of 36. The unapologetically wild singer and musician who inspired one or more generations of punk and alternative rockers, many of whom pattered themselves in his image, hadn't been so lucky in attempts to revive his own career. Singers like Conway Twitty and Jerry Lee Lewis had already made successful transitions into country music, but Gene Vincent doggedly stayed as close as possible to the rock and roll path he'd helped pave. For the fans that were there at the outset, and the younger generation that came to the boppin', crazy-leg party later, he's a legend. And the rest...whether they're fans or not...are, at the very least, aware of his position as one of rock and roll's greatest.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Be-Bop-A-Lula /

Woman Love - 1956 - Race With the Devil /

Gonna Back Up Baby - 1956 - Bluejean Bop /

Who Slapped John - 1956 - Crazy legs - 1957

- B-I-Bickey-Bi, Bo-Bo-Go - 1957

- Lotta Lovin' /

Wear My Ring - 1957 - Dance to the Bop - 1957

- I Got a Baby - 1958

- Baby Blue - 1958

- Rocky Road Blues - 1958

- Git It - 1958

- Say Mama - 1958

- Who's Pushin' Your Swing - 1959

- Wild Cat - 1960

by Gene Vincent - Hy Heart - 1960

by Gene Vincent - Pistol Packin' Mama - 1960

by Gene Vincent and the Beat Boys - If You Want My Lovin' - 1961

by Gene Vincent - She She Little Sheila - 1961

by Gene Vincent - I'm Going Home (To See My Baby) - 1961

by Gene Vincent with Sounds Incorporated - Unchained Melody - 1961

- Lucky Star - 1962

by Gene Vincent and the Dave Burgess Band - The King of Fools - 1962

by Gene Vincent - Crazy Beat - 1963

by Gene Vincent - Humpity Dumpity - 1964

by Gene Vincent - La-Den-Da Den-Da-Da - 1964

by Gene Vincent - Bird-Doggin' - 1966

by Gene Vincent - Lonely Street - 1966

by Gene Vincent - Born to Be a Rolling Stone - 1967

by Gene Vincent - Story of the Rockers - 1968

by Gene Vincent - Be-Bop-A-Lula '69 - 1969

by Gene Vincent - Sunshine - 1971

by Gene Vincent - The Day the World Turned Blue - 1971

by Gene Vincent