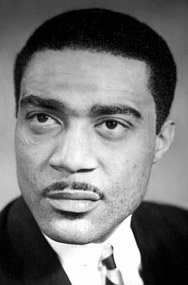

ANDRE WILLIAMS

Bacon Fat

It figures that anyone who has a desire to be a singer, yet possesses vocal limitations that would make such a career unlikely, would either abandon the dream...or find a way to work around the problem. Andre Williams, well aware his throaty voice produced scratchy, off-key sounds, found the solution was to talk, not attempting to hit notes but to simply tell stories over a rhythmic background, an idea uncommon enough in the early '50s that those close to him insisted he would never make it. Years later, when asked about his offbeat style, he admitted he would never be able to compete with the many fine singers of his era, much less an R&B headliner like Clyde McPhatter or Ray Charles. So he spoke the lyrics while focusing on songwriting, producing and promotion. What resulted was a lifelong career on the fringes of the music industy from which he made an adequate living doing the the things he was actually good at.

Born Zephire Williams in the city of Bessemer just south of Birmingham, Alabama, young "Andre" spent much of his childhood moving between Chicago, Illinois and his birth state. His mother passed away in 1943 when he was just six years old, after which he lived with his southern grandparents, ploughed their fields, and was only allowed to listen to country music. At 13 he returned to Chicago to live with his father and took many odd jobs that usually interfered with his schooling; truancy issues landed him in juvenile facilities more than a few times. He yearned to be a singer like his idol, Hank Williams, but exposure to some of the big city blues shouters gradually adjusted his preference. In 1951, at age 14, Andre hatched a plan to enlist in the Navy using his older brother's birth certificate...and it worked for a year or so, until his brother got his draft notice and the fraud was revealed. A court martial ensued, several months were served at the Fort Leavenworth facility in Kansas, then Andre found himself on the streets at 16 with a dishonorable discharge.

But he didn't return to Chicago. A previous visit to Detroit convinced him better opportunities existed there for a young singer. The Warfield Theater, besides its fame as a venue for the hottest stars of jazz, staged regularly scheduled amateur contests. Williams, already self-conscious about his vocal rasp, entered as a dancer and caused quite a ruckus with his unskilled but bold moves based partly on Cab Calloway's routine in the 1943 musical film Stormy Weather but with a few slightly dangerous backflips added for effect. Word got around as he perfomed once each week for the next two months. Devora Brown, owner of the struggling Fortune record label, came by out of curiosity and offered him a record deal; she didn't seem concerned about his singing ability or lack thereof.

Jack Brown and his wife Devora (an "old Jewish lady," as Andre affectionately described her) had started the Fortune Record shop and label in 1946. Achieving marginal success in 1953 with The Davis Sisters (Betty and Skeeter), they had just signed The Diablos, featuring lead vocalist Nolan Strong, when Andre came along. A small room behind the record shop functioned as a recording studio (with just an Ampex tape recorder and several RCA microphones); later, Andre did some backing vocals for The Five Dollars. His first single for the company was billed as Andre Williams (Mr. Rhythm) and the Don Juans (a name the Five Dollars used when they backed him); autumn '55's "Going Down to Tia Juana" (he penned it with Mrs. Brown) reveals a solid lead vocal by Williams, though he would have argued the point if you'd tried to compliment him. A raw single-take performance with prominent handclaps and a fun feel, it was a good start for the aspiring R&B flim-flammer.

Devora Brown was game for anything Andre wanted to do. He composed the next Five Dollars single, "You Know I Can't Refuse," then made many attempts at getting the master of "Bacon Fat" just right, a song inspired by a sandwich he once got at a diner '...down in Tennessee.' Due to his discomfort as a singer, he employed a talking jive backed by a gutbucket sax riff: 'Have mercy...awww, but the chicken was never like this!'...and whatever other lyrics came to mind (some called it rap...but only after a few decades had passed). It became a dance '...where you wind up twice and then ya end up with a bump!' and the Don Juans kept it tight, chanting 'didlee, didlee womp, womp' (which became the title of some reissue pressings). Regional stations started picking up on the record in early 1957 and soon demand was more than the Browns could handle. Columbia took over distribution, sending it out on Epic, getting the song into the national R&B top ten in February. The talking approach worked. Andre had a hit!

The Five Dollars did a takeoff on Fortune called "How to Do the Bacon Fat" that did little to further explain the moves. Andre passed on the opportunity to record a follow-up with Epic, staying with Fortune out of loyalty and assurance from the Browns that they would be able to handle distribution of the next single. "Jail Bait" didn't catch on as expected, possibly due to its touchy subject concerning illicit goings-on with underage girls ('17 and a half is...still...jail bait...'). Andre's routine, trying to beat the charge by pleading with a courtroom judge to no avail, came off as humorous but disturbing. Later efforts were of the lighter-hearted dance variety, such as "The Greasy Chicken," a dialect-challenged romp ("greasy" is translated into Chinese as..."greasy") that went beyond spoken word with weird barnyard animal sound effects (these songs were more admired when reissued and exposed to a younger rock-fan base in the 1970s). Williams mentored a young singer named Gene Purifoy, who changed his name to Gino Parks and joined him in his post-Fortune phase.

Andre remained with Devora's label until 1960. The following year, he and Gino signed separate contracts with Detroit's rising Tamla/Motown operation. Parks had just two singles issued a year apart, while Andre Williams cut two sides that went unheard. A few songs he'd written were recorded and released, including "If Cleopatra Took a Chance" by Eddie Holland and "Mo Jo Hanna" by Henry Lumpkin and the Love Tones. He produced some of The Contours' sessions and scored decent royalties with the flip side of a major hit: "Oh Little Boy (What You Do to Me)," an unusual (and delightful) track by Mary Wells, backed her chart-topping "My Guy." Andre's relationship with label boss Berry Gordy was hit-and-miss; he had better luck moonlighting at smaller Detroit labels (and continued working with Wells after she left Motown for 20th Century-Fox). When Gordy passed on "Shake a Tail Feather," a song he'd written for the Contours, he took it to Otha Hayes and Verlie Rice at One-derful! Records (both of whom claimed composing credit, yet had nothing to do with writing it). The wildly infectious dance tune by The Five Du-Tones was a hit in the summer of '63. Then "Twine Time" (co-penned by Rice), on the affiliated Mar-V-Lus label, made an even bigger splash for Alvin Cash and the Crawlers in early '65. At the same time, Williams produced Sir Mack Rice's "Mustang Sally" for Blue Rock Records.

Making a return as an artist, he put together an orchestra, bypassing the talking vocals on several instrumentals. "Rib Tips" (another food-related song!) reached the Billboard pop charts on the short-lived Avin label in January 1966; similar efforts appeared on Avin and Wingate, some featuring spoken asides. He then produced early releases for later Stax-Volt stars The Dramatics (on Wingate) and soon-to-be Motown hitmaker Edwin Starr (on Ric-Tic) before re-entering the charts in July '67 with his own Sport label single, "Pearl Time" (essentially "Bacon Fat" with a new set of lyrics). Heading back to Chicago, he signed with Chess Records and had several singles on the Checker imprint, most notably "Cadillac Jack" ('sho was a mack...'), a funky cinematic ghetto tale that briefly made the R&B chart in October 1968. True to form, he moonlighted again, co-composing Bull and the Matadors' top 40 "Funky Judge" that year and producing a pair of singles at Duke in '69 for Bobby "Blue" Bland.

Andre Williams was never a quitter. Between 1970 and his death in 2019, he worked with Ike and Tina Turner, then was sidelined by a serious drug addiction (that he kinda-sorta blamed on Ike) before emerging in the 1980s, as vibrant as ever, surpassing everyone's expectations. Lux Interior of The Cramps had long been a fan and helped get him reconnected, albeit in rock circles. He worked with bands like The Sadies and The Dirtbombs and reunited with earlier peers The Mighty Hannibal, Ronnie Spector, Rudy Ray Moore, saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood and guitarist and longtime collaborator Dennis Coffey. He kicked off the new century with 2000's Black Godfather, following with a new LP nearly every year through 2016 when his final album appeared sporting a full-circle-type title: I Wanna Go Back to Detroit City.