DINAH WASHINGTON

At some point in Dinah Washington's career she was nicknamed "The Queen of the Blues." The majestic designation stayed with her, though it became less accurate as her style evolved. Certainly the blues was at the root of her music, simply considering the many stormy relationships she went through that likely provoked her well-known mood swings; but her blues recordings take a back seat to a stronger preference towards jazz. Ultimately she recorded many popular standards and even country songs; she adjusted them to suit her own sensibility and excelled. Dinah often proclaimed, for all within earshot to hear, "I can sing anything!"...and as long as she wasn't called upon to perform an operatic aria, the statement was true. Time and again she backed up those words with disciplined vocals resulting in near-perfect performances at every turn, delivered with an apparent effortlessness regardless of the quality of the material she was given. For nearly two decades her personality, stage presence and stunning vocal ability captivated black audiences and, eventually, music fans from all walks of life, right up until her life abrupty ended several months before what would have been her 40th birthday.

Born Ruth Lee Jones in Tuscaloosa, Alabama in 1924, she moved to Chicago with her mother at a very early age. Her first musical interest was in the spirituals she heard at church; she practiced piano during those years and became quite accomplished, a fact often overlooked in view of her more obvious emphasis on vocals. For a couple of years in the early 1940s she sang with The Sallie Martin Singers, a popular Windy City gospel group, though just prior to this, at age 15, she had won an amateur singing contest at Chicago's famous Regal Theater. Even as a youngster Ruth was strong-willed, stubborn and argumentative, but these qualities (or faults, if you will) weren't suitable traits for a gospel singer, so she decided to try and make her way in the world of jazz.

Almost immediately, club owners recognized her exceptional talent. She played piano and sang in a number of Chicago nightclubs while still in her teens, places like the Rhumboogie Cafe, a nightclub co-owned by then-current heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis. It was at the Garrick Lounge in downtown Chicago that she got her big break. An unplanned performance one night with the popular Chicago-based group The Cats and the Fiddle led to regular appearances at the club; Lionel Hampton then invited her to sit in with his band at the Regal, which went so well that she was hired as a female counterpart to Hamp's lead singer, Joe Williams. Ruth changed her name to one she felt was more grandiose; "Dinah," a song introduced by Eddie Cantor in the musical Kid Boots, had been a hit for Ethel Waters (and others) in 1926 and was a favorite of hers; Washington sounded about as royal as any American name could be, seeing as how it was the surname of the first U.S. president. She claimed to have come up with it herself, but Hampton, her manager Joe Glaser and Garrick owner Joe Sherman have all, at various times, taken credit for the idea.

"Evil Gal Blues" ('I'll empty your pockets and fill you with misery') was her first release from a four-song session, produced by Leonard Feather for Keynote Records, that featured pianist Milt Buckner, trumpeter Joe Morris, tenor saxophonist Arnette Cobb and other moonlighting members of Hamp's band credited on the label as, simply, Sextet; it was a hit on Billboard's Harlem Hit Parade (precursor to the rhythm and blues chart) in April 1944, but only after her second disc, the mildly risque "Salty Papa Blues" (both songs were penned by Feather), had reached the chart. Some reviewers compared her favorably to Billie Holiday, which pleased her, as Billie was the singer she had initially patterned herself after. Technically she was under contract to Lionel Hampton, so any other releases at that point were contracted to appear on the Decca label under Hampton's name. In December 1945 she slipped away from Hamp and recorded 12 songs with a lineup of future jazz legends: saxophoist Lucky Thompson, vibraphone player Milt Jackson and bassist Chares Mingus.

Permanently parting with Hampton at the first opportunity, having made up her mind to be a solo singer, she was anxious to call her own shots. She signed with the recently-founded Mercury Records, headquartered in Chicago, and quickly discovered the desired freedom of musical expression that had been nonexistent with Hamp was only slightly less restrictive with the new label. Her first sessions for Mercury took place in January 1946 with Gus Chappell's orchestra, but success was limited that first year. "Blow-Top Blues," recorded earlier with Hampton, featured curiously fantastic lyrics penned by Feather ('Last night I was five feet tall, today I'm eight feet ten...and every time I fall down stairs I float right up again...'); in May 1947 it landed in the R&B top ten, helping solidify Dinah's name as a solo singer and ensuring, at least, a full calendar of club appearances.

A remake of "Ain't Misbehavin'," Fats Waller's signature song from 1929, became her first hit for Mercury in the spring of 1948, more than two years after her label debut. That hit and "West Side Baby," both recorded with The Rudy Martin Trio, kicked off a steady roll of bluesy jazz hits; "Resolution Blues," backed by the Cootie Williams band, preceded more Martin Trio tracks including "Am I Asking Too Much," a number one Juke Box Race Records hit, her first song to top a national chart, in October '48. Follow-up "It's Too Soon to Know" was one of several tracks that featured oboe playing by Mercury A&R director Mitch Miller (a far cry - some would say downgrade - from his earlier work as a classical concert soloist). With seven hits in 1948, Dinah was on an out-of-the-blue red-hot streak.

In '49 she had her biggest hit yet with drummer Teddy Stewart's band. "Baby, Get Lost" was number one in September on Billboard's newly-named Best Selling Retail Rhythm and Blues Records chart. Dinah's early blues was gradually being replaced by more commercial R&B, but this single proved there was still a demand for her mildly raunchy ('I'd try to stop your cheatin', but I just don't have the time...'cause I've got so many men...that they're standin' in line...'), attitudinal ('...any time I'm ready, I can tell you baby, get lost!'), blues-oriented material. The record's nearly-as-popular flip, "Long John Blues," was, perhaps, her most scandalous effort yet (as pertains to a dentist: 'He took out his trusty drill and he told me to open wide...he said he wouldn't hurt me but he'd fill my hole inside...Long John, Long John...you've got that golden touch').

Dinah was exacting in her approach to performing. A demanding bandleader, she insisted everything had to be just right; if a musician missed a note, for example, she would reprimand him for it, to his embarrassment, during the performance. If clubgoers got too rowdy, she would admonish them as well...which only fueled their fascination with her. But in the '50s, Mercury executives latched onto a successful formula that projected a different type of singer than the patrons of her live shows witnessed her to be. Popular songs were assigned to Dinah for single release, resulting in a seemingly endless parade of pop cover versions targeting the rhythm and blues market (an antithesis to the more commonly perceived notion that white artists routinely covered hits by black artists), giving Dinah one top ten hit after another, some two dozen between 1950 and '55. The Andrews Sisters' 1950 hit "I Wanna Be Loved," Hank Williams' country wonder "Cold, Cold Heart" (a million seller for Tony Bennett in '51) and Kay Starr's signature '52 smash "Wheel of Fortune" all received the Washington treatment and were R&B hits, despite being handled with a professionalism that was, nevertheless, by-the-numbers.

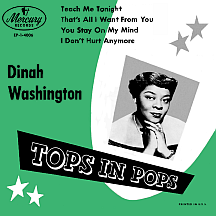

Her primary competition during the early '50s came from Atlantic's Ruth Brown, who scored several number one R&B hits with original, and more overtly rhythmic, material. Dinah strayed from her imposed pop ballad mindset, venturing into Brown's territory for one two-sided 1953 hit, "TV is the Thing (This Year)," a timely tune with humorously suggestive technology-versus-sexuality double-entendre references, backed with "Fat Daddy," describing a plus-sized lover possessing skills on par with the "Salty Papas" and "Long Johns" of years gone by. Many of her recordings during this time featured the fabulous tenor saxophonist Paul Quinichette; she also worked regularly with drummer Jimmy Cobb (while having an on-again, off-again affair with him). In 1954, Mercury assigned Hal Mooney, a versatile producer and arranger with extensive big band experience, the task of producing her recordings. The label put its trust in Mooney to bring out the best in several of their their female vocalists (he also worked with Sarah Vaughan at this time and produced some of Nina Simone's best material a decade later); still, this resulted mainly in the types of cover versions Dinah had become used to. "Teach Me Tonight" (a pop hit for Cuban trio The De Castro Sisters) and "That's All I Want From You" (Jaye P. Morgan's top seller) were R&B hits for Dinah in 1955, each performed in a more sensuous manner than the original. The pop cover game plan had paid dividends for several years but was about to run its course.

In 1955, hotshot 22-year-old Quincy Jones arranged a little ditty for Dinah called "I Diddie," double-tracking her voice on a catchy nonsense-syllable song, the highlight among a handful of mid-charting mid-'50s Washington releases that preceded her disappearance from the charts. Offsetting any lack of control the record company gave her in the studio, she proficiently handled the live aspect of her career. Eddie Chamblee, a former Hampton band player she'd known since high school in Chicago, became her fifth husband (but who's counting?) in March 1958. She made him her bandleader in keeping with a pattern she'd developed of hiring her various husbands and/or lovers, most of them musicians, to play in her band. Chamblee (a saxophonist who'd been featured on Sonny Thompson's chart-topping 1948 R&B hits "Long Gone" and "Late Freight") wasn't known for singing, yet he duetted with Dinah on "Everybody Loves My Baby," an unsuccessful single in 1957; a similar project with future Mercury star Brook Benton would reap extreme benefits a few years later. Dinah and Eddie, by the way, got divorced before their first anniversary rolled around.

From '55 to '58, Dinah was visible mainly as a touring act. She made several appearances at Rhode Island's annual Newport Jazz Festival and one such performance, from July 1958, can be seen in Bert Stern's great film Jazz on a Summer's Day; while singing "All of Me," she demonstrates some measure of skill at an instrument other than piano, as she elbows vibraphonist Terry Gibbs and the two hammer away together on the vibes, a musical moment pricelessly preserved on celluloid. Dinah was on the verge of a career resurgence; Mississippi-born songwriter-producer Clyde Otis, hired by Mercury Records at about that time for the position of creative director, had ambitions beyond making records for the black audience. Amazingly, the majority of music fans remained segregated in the late '50s, and I'm not talking about generational differences. Otis was ready to do his part to break down the walls. Dinah Washington was about to cross over to mainstream stardom.

When Clyde Otis took the A&R position with Mercury, he altered longstanding company rules and began producing black singers (Vaughan, Benton and others) with an eye towards promoting them to all radio formats and positioning them to be allowed to perform in any venue. Turns out the timing was right and Mercury reaped the benefits (in addition to competing record companies who were also expanding their operations in similar ways). "What a Diff'rence a Day Makes" seemed an unlikely vessel for Dinah's ascendancy to the next level. The song's origin is unique; it was originally composed in Spanish (as "Cuando Vuelva a Tu Lado") by Maria Grever, a songwriter from Mexico City who became very successful in the U.S. during the 1920s and '30s, achieving a notoriety for being the first woman from Mexico to break through in such a way. English lyrics were written by New Yorker Stanley Adams and this new version (titled "What a Difference a Day Made") became a hit in 1934 for The Dorsey Brothers Orchestra. Otis produced the song for Dinah with a string arrangement by Belford Hendricks (the same team had given Brook Benton his first major hit a couple of months earlier); her recording reached the top ten of the R&B charts in July 1959 and went top ten pop the following month.

"Unforgettable," a song closely associated with Nat "King" Cole, came next and worked the same magic for Dinah. She'd cast a much wider net over the music world through these lush Otis-Hendricks productions; jazz critics fumed (as they had in previous years when she began covering pop songs), but you can argue just so much with success. She toured Europe for the first time, performing for receptive fans, the majority perhaps unaware of her existence just months before. In November, Dinah won a Grammy for "What a Difference a Day Makes" in the category Best Rhythm and Blues Performance. Then Otis paired her with Benton and two major hits resulted, born amidst an air of tension in the studio. Dinah, ever the prepared professional, wasn't in sync with Brook's more casual approach to making records. During the recording of "Baby (You've Got What it Takes)," Benton flubbed a line and Washington ad-libbed her own reply ('You're back in my spot again, honey!') that suggested he'd messed up the line during a previous take. In the end, the company chose to release the "mistake" version; a similar, less-ad-libbed approach was used in at least one take of "A Rockin' Good Way (To Mess Around and Fall in Love)," and that was released as well for the follow-up. The playfulness one hears is actually anything but, and the two never worked together again.

Both records were major hits. "Baby," in fact, spent ten weeks at number one on the R&B charts (becoming the biggest hit of Dinah's career) and went top ten pop as well; "A Rockin' Good Way" was also a number one R&B/top ten pop smash. Booking concerts together would have been ideal at this point to further the popularity of both singers, but Dinah wouldn't stand for it. At her own stage shows, where she was often casual about revealing certain details of her life between songs, she began commenting on Benton's inability to "get the words right" during the recording session, unconcerned with the repercussions that might result from badmouthing the artist she was currently co-ruling the charts with. But what did she care? She was the Queen!

There were more solo hits over the next year or so as Dinah recorded with a number of talented orchestra leaders and musicians, all working within the framework of Hendricks' string arrangements. "This Bitter Earth" (composed by Otis) hit number one R&B in July 1960, just after "A Rockin' Good Way" had wrapped its run at the top. Conductor Nat Goodman accompanied her on "Love Walked In," a hit in the fall. "We Have Love" and "Early Every Morning (Early Every Evening Too)," recorded with Fred Norman's orchestra, were arranged by Belford to sound just like the Benton duets, only with Dinah solo. Around this time she squeezed in another marriage, to Blackboard Jungle actor Rafael Campos, who was nearly 12 years her junior. He was long gone by late 1961 when she had her last big hit for Mercury, "September in the Rain," an Otis-ized revival of Harry Warren and Al Dubin's classic tune from 1937.

But something wasn't right; since the Benton brush-up she felt she wasn't being treated like her sovereign-sounding nickname suggested she should. Soon afterwards Dinah left Mercury, after 16 years and more than four hundred recordings for the label, and signed with Roulette Records. Continuing to work with Fred Norman as the arranger on some of her Roulette projects, she scored a top 40 hit right off the bat with yet another '30s tune, the Jimmy McHugh-Harold Adamson song "Where Are You," in June 1962. But despite a profusion of recordings made during her short stay at Roulette, there were no further hits. Songs like McHugh and Adamson's "You're a Sweetheart" and arranger Don Costa's energetic production of "Soulville" (which she cowrote with Titus Turner, Henry Glover and Morris Levy) made brief appearances on the charts; the latter, from the spring of 1963, turned out to be her swan song.

Dinah Washington had seven marriages, some lasting as little as a few months, none more than a few years ("I change husbands before they change me," she reasoned). Her last husband, Richard "Night Train" Lane (a football star who holds the NFL's all-time record for the most interceptions in a single season, accomplished during his '52 rookie year with the Los Angeles Rams), with whom she'd tied the knot just five months earlier, was present at the time of her death. An escalating prescription drug habit (she took so-called "diet pills" on a regular basis, though they didn't necessarily produce the desired result) and increased dependance on alcohol proved to be a lethal combination. On the morning of December 14, 1963, Lane awoke to find she had passed. A great era in music history passed with her.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Salty Papa Blues - 1944

by Sextet with Dinah Washington - Evil Gal Blues - 1945

by Sextet with Dinah Washington - Blow-Top Blues - 1947

with Lionel Hampton and his Septet - Ain't Misbehavin' - 1948

- West Side Baby - 1948

- Resolution Blues - 1948

- Walkin' and Talkin' - 1948

- I Want to Cry - 1948

- Am I Asking Too Much - 1948

- It's Too Soon to Know - 1948

- You Satisfy - 1949

- Baby, Get Lost /

Long John Blues - 1949 - Good Daddy Blues - 1949

- I Only Know - 1950

- It Isn't Fair - 1950

- I Wanna Be Loved - 1950

- I'll Never Be Free - 1950

- I Won't Cry Anymore - 1951

- Cold, Cold Heart - 1951

- Wheel of Fortune - 1952

- Trouble in Mind /

New Blowtop Blues - 1952 - TV is the Thing (This Year) /

Fat Daddy - 1953 - I Don't Hurt Anymore /

Dream - 1954 - Teach Me Tonight - 1955

- That's All I Want From You - 1955

- If It's the Last Thing I Do /

I Diddie - 1955 - I Concentrate on You - 1955

- I'm Lost Without You Tonight - 1955

- Soft Winds - 1956

- Everybody Loves My Baby - 1957

with Eddie Chamblee - Make Me a Present of You - 1958

- What a Diff'rence a Day Makes - 1959

- Unforgettable - 1959

- Baby (You've Got What It Takes) - 1960

with Brook Benton - It Could Happen to You - 1960

- A Rockin' Good Way (To Mess Around and Fall in Love) - 1960

with Brook Benton - This Bitter Earth - 1960

- Love Walked In - 1960

- We Have Love - 1960

- Early Every Morning (Early Every Evening Too) - 1961

- Our Love is Here to Stay - 1961

- September in the Rain - 1961

- Tears and Laughter - 1962

- Where Are You - 1962

- I Want to Be Loved - 1962

- For All We Know /

I Wouldn't Know (What to Do) - 1962 - You're a Sweetheart - 1962

- Soulville - 1963