THE MIRACLES

Motown didn't start with The Miracles. Well, it sort of did, but what became Detroit's most famous record company actually had its beginning when label founder Berry Gordy began writing and producing Jackie Wilson's hits for Brunswick Records in 1957. Later, Marv Johnson got the same treatment as Wilson, for United Artists. But when Smokey Robinson and his three best friends (and girlfriend) came along, that's when Gordy found the act that would get his Tamla label going in a big way. Thanks in large part to the Miracles, Motown became a major force.

William Robinson was nicknamed "Smokey Joe" by one of his uncles when he was very young. Since William had light skin, his uncle wanted to give him a reason to always remember his race and heritage. When Smokey was ten years old, in 1950, his mother, Flossie Robinson, passed away, leaving him in the care of his older sister Gerry. Big sis loved music and in her eyes no one topped "The Divine One," Sarah Vaughan. Smokey listened to her music more than any other during his adolescence, never less than impressed; it was tantamount to being taught how to sing by one of the foremost practitioners of the craft. In 1952, when The Dominoes' smash "Have Mercy Baby" hit the airwaves, he was enthralled by the song's wildly unconstrained lead singer, Clyde McPhatter, later seeing him perform at the Broadway Capitol Theater (now the Detroit Opera House). Through Vaughn's singing he learned much about phrasing and the feeling that goes into delivering a song. Through McPhatter he realized that a male singer with a high voice need not be embarrassed by it; Clyde's success gave him confidence.

Claudette Rogers didn't considered a music career right off the bat. Her family moved to Detroit when she was eight years old. Older brother Emerson "Sonny" Rogers, on the other hand, dreamed of being a singer and his love of music rubbed off on Claudette. Then she met Smokey and the two started going together. He was 15, about two years older than she. About this time, Smokey and a few of his buddies at Northern High School started a vocal group called The Five Chimes. A few early members came and went, and by 1956 the lineup consisted of Sonny, Smokey, Ronnie White, Warren Moore (known to everyone as Pete) and Bobby Rogers (who not only was born in the same hospital as Smokey, but on the same day!) After awhile, they decided to change the group's name to something a bit more dashing, The Matadors, and before you know it Claudette put together her own girl group equivalent, The Matadorettes, with a couple of her friends. Mostly this was just posturing on the part of everyone concerned; the real work, that of actually singing, and singing well, was still ahead.

Berry Gordy was running his own jazz-oriented record store, the 3 Dimension Record Mart, at about this same time, but owning a business was more of a struggle than he had anticipated and it eventually closed. He caught a few breaks in his attempts at a music career and met Jackie Wilson, which led to a string of hits he and Tyran Carlo composed for the singer. In the summer of 1957, Jackie's manager, Nat Tarnopol, was holding auditions and the Matadors (now including Claudette, who replaced her brother Sonny when he went into the Army) showed up in the hopes of dazzling him with their talent. All he could see, though, was a juvenile version of The Platters and he showed them the door. As luck would have it, Gordy was in the building that day and heard the audition. He approached the group afterwards and offered to help them. Smokey, who had been writing songs for some time, welcomed Gordy's advice...the more critical the better.

After a time working with the group, who had decided on another name change to The Miracles, Smokey came up with "Got a Job," an answer to The Silhouettes' number one hit "Get a Job." Gordy and Carlo reworked the song and the group recorded it at the United Sound Studio in the heart of downtown Detroit. Gordy struck a deal with George Goldner, who released it on his End Records label and while not a national hit, it went over well locally in the spring of 1958 and was followed by another single on End, "I Cry." Some changes took place for Berry Gordy in 1959, as his association with Jackie Wilson ran its course when he and Tarnopol clashed. He moved on and began writing and producing songs for Marv Johnson.

Smokey has told the story of the time Gordy was complaining about being at the mercy of "the man." Smokey's reply was, "Why don't you be the man?" Always one to consider advice from others, Gordy took Smokey's words to heart and, with an 800 dollar loan from family members, he started Tamla Records, named in part after the Debbie Reynolds hit "Tammy." Johnson's "Come to Me" was the first Tamla release, a hit in Detroit and eventually nationwide, but distribution demands forced him to license Johnson's masters to United Artists, who ultimately reaped most of the monetary benefits.

Smokey kept throwing out ideas, searching for the next song that would get the Miracles back into a studio and hopefully onto the charts. "Bad Girl" had the most sensitive lyrics Gordy had heard yet from his young protege. They returned to United Sound and cut the track, but United Artists Records wasn't interested nor, it seems, was any other label in New York. He sold the masters to Chess Records of Chicago and the single became the first Miracles record to hit the national charts, in October 1959. It had a brief run, but did wonders for the group's confidence, though tempered by a lack of stage presence the group had, which culminated in a disastrous appearance at New York's Apollo Theater where the five singers basically stumbled over each other and showed zero coordination. The act's recording side was coming together; the performing side still needed a lot of work.

Trying a different gimmick, Smokey and Ronnie White did a one-off single on Tamla that was also released on the Argo label, a Chess subsidiary. "It," a strange but cute story about a mysterious creature, was credited to Ron and Bill, but was unsuccessful; perhaps it was too strange. The future of the tightly-knit five-member Miracles was not in jeopardy. One more Chess single, "All I Want (Is You)," came out at the end of the year.

With the minor success of "Bad Girl," Smokey felt validated...but Berry was frustrated. He redoubled his efforts to establish Tamla as a major player, not just in the Great Lakes region, but across the nation. He lined up distributors, hired a crack promotion man, moved into his own facilities on West Grand Boulevard and made other decisions designed to affect the future of the company in what would hopefully be a positive way. But he needed a big hit. When Smokey presented his composition of "Way Over There," Gordy felt it could be the one, but there were problems: after the first take had been pressed and distributed, he decided he wasn't happy with it and put everyone through the process of rerecording the song with added strings for a bigger sound. The first pressings were recalled, the record was redistributed, and the delay probably played a large part in killing its momentum.

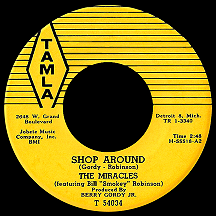

When "Shop Around" was released, it was a midtempo number with a message that basically advised playing the field before settling down. But again, Gordy wasn't satisfied; it needed something extra. This time he called everyone in during the middle of the night to redo the song with a bigger band. The pianist apparently went back to sleep, so Gordy played piano when he failed to show. The new uptempo take had a much more polished sound and everyone was encouraged about its chances. The record was reserviced in December 1960 and went all the way to number one on the R&B charts in January '61, climbing to a number two peak on the pop charts the following month. Motown had its first major hit.

The early records were usually written in rough form by Smokey with input and improvements from Gordy. By 1961, Smokey was getting the hang of it and Gordy began leaving him to his own devices. The group worked hard at improving their stage moves (while Gordy made his own first moves to establish an in-house artist development department to ensure future acts would be ready for public appearances when the time came). Smokey met guitar player Marv Tarplin, who'd been working with girl group The Primettes, a quartet that later, as chart-topping trio The Supremes, led the Motown pack. He lured him away for some live shows and Tarplin fit right in, becoming a sixth member, sort of an "honorary Miracle." He worked closely with the group from that point on and later with Smokey when he went solo.

Following "Shop Around" was difficult. Records like "Ain't it, Baby," "Mighty Good Lovin'" and "Everybody's Gotta Pay Some Dues" weren't out-and-out bombs, but lacked the spark of the one major hit, though some efforts were outstanding. The heart-tugging, romantic Smokey songs "What's So Good About Good-by" and "I'll Try Something New," on the other hand, hit the right emotional buttons and were top 40 hits in 1962. Smokey convinced Gordy, who had been recording his own compositions with Mary Wells, to let him try his hand with her, which resulted in top ten smashes like "The One Who Really Loves You," "You Beat Me to the Punch" and "Two Lovers." Thanks largely to Smokey's songs, tailor-made to her talent, Mary surpassed the Miracles in 1962 and '63 and was Motown's most successful act during that period.

In October 1962, the Miracles headlined the first Motortown Revue, a grueling, seemingly never-ending bus ride from venue to venue for the acts, but a key component in exposing the music and artists of Tamla and Motown from coast to coast. Smokey took more control of the group's fate (almost three years since "Shop Around" had been the group's only top ten hit, he was doubting whether they could ever again reach similar heights) and began producing while continuing to write the songs. "You've Really Got a Hold on Me" did the trick ('I don't like you, but I love you...though I wanna split now, I can't quit now...'), returning them to the pop top ten and number one spot on the R&B charts in February 1963. The Beatles, Miracles fans themselves, included a version of the song on their second album With the Beatles, spreading the word overseas. While composing his relatable romantic vignettes, Smokey often embraced cliches ('...sugar and spice, everything nice...') and the public gradually warmed up to them; before long, the Miracles would be so solidly established that getting a hit with each release would be the rule rather than the exception.

The Miracles took a brief detour in 1963, recording a couple of songs by Eddie Holland, Lamont Dozier and Brian Holland (later the guiding force behind Martha and the Vandellas, Four Tops and especially the Supremes). "Mickey's Monkey" was a pure dance track, a departure from the group's norm, and their third top ten hit, sharing space in the summer of '63 with Major Lance's "Monkey Time" as the dance of simian preference swept the nation. The Holland-Dozier team adhered closer to Smokey's formula with the follow-up, "I Gotta Dance to Keep From Crying." Success intermingled with tragedy, though, when Smokey came down with a serious case of the Asian Flu, forcing him to miss a tour of the southern states. Claudette, pregnant at the time, somehow managed to cover for him as lead singer, but an auto accident between dates took the life of driver Eddie McFarland and caused Claudette to miscarry (a recurring problem, as the couple seemed unable to bear children in their early years of marriage).

Smokey enjoyed a rewarding second career in the mid-1960s, writing hit after hit for some of Motown's best acts. Mary Wells went to number one with "My Guy." The Temptations scored their first major hit with one of his songs, "The Way You Do the Things You Do," at first resisting what they felt were corny lyrics, later catching on to Smokey's consistently clever way with a rhyme. Several other Robinson-penned hits followed, including "My Girl" (a spinoff of the Mary Wells chart-topper), the first number one smash for the Tempts. Some of his contributions to The Marvelettes made a little chart noise in '63 and '64, then after a slow mid-'60s stretch they came back strong with Smokey's "Don't Mess With Bill" (his own personal ego-stroke) and continued later in the decade with "The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game," "My Baby Must Be a Magician" and others.

Meanwhile, the Miracles, including Marv Tarplin, were all throwing ideas into the songwriting mix for their own releases. Mid-'60s hits like "Ooo Baby Baby," "The Tracks of My Tears" and "My Girl Has Gone" were credited to two, three, or as many as five of the six Miracles on any given single. Smokey was the star, but the end product was a genuine group effort. Smokey continued contributing to the success of others as a producer and writer; Brenda Holloway had one of her biggest hits with "When I'm Gone" in '65. The Contours' "First I Look at the Purse," humorously (and somewhat offensively) stating that a woman's looks don't matter as long as she has money, fell outside the usual sensitive parameters of Smokey the songwriter. He and various Miracles also wrote songs for Motown superstar-in-the-making Marvin Gaye in '65 and '66, most notably "Ain't That Peculiar" and "One More Heartache."

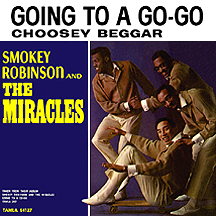

In 1966, Gordy (who called all the shots, after all) began playing with the idea of billing the group as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles (shown as such on the covers of both the album and 45 sleeve for "Going to a Go-Go"). The "Go-Go" single still showed the Miracles on the label as was the case with "Whole Lot of Shakin' in My Heart (Since I Met You)" (written by Frank Wilson) and "(Come 'Round Here) I'm the One You Need" (another Holland-Dozier-Holland song). The transition was gradual and the other group members were supportive of it. They all agreed: Smokey was the star. Apparently, they also had no problem with really long song titles. With "The Love I Saw in You Was Just a Mirage," in early 1967, the transition was complete and Smokey's name appeared above the group's for the rest of the time they were together.

One other big change occurred in 1966: Claudette left, at least as far as live performances went. Long since dubbed the "First Lady of Motown" by Gordy (having been the first woman he signed to a contract), she continued to record with the group well into the 1970s. The couple's attempts at having a family were not for naught either; displaying their deep loyalty to the company, son Berry was born in 1968, followed by daughter Tamla in 1970.

The late 1960s was a period of great expansion for Hitsville U.S.A. Several superstar acts were at the peak of their powers and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles were right in the thick of all the action. "More Love," "I Second That Emotion," "Special Occasion," "Baby, Baby Don't Cry"...the list goes on and on. The one thing missing was a number one pop hit, something most of the label's top acts had achieved. In the summer of 1970, Motown's label in England, Tamla Motown, released a 1967 album cut, a Henry Cosby-Stevie Wonder song with lyrics by Smokey, "The Tears of a Clown." It hit number one in the U.K. in September, then was immediately released in the U.S., reaching the top of the charts in December.

Smokey had been planning to quit the group, having grown tired of the demands of touring, hoping to give himself more time to spend with his wife and young children. As it turns out, he remained with them until 1972. The Miracles forged ahead with a new lead singer, Billy Griffin, scoring major hits in the mid-'70s with "Do It Baby" and "Love Machine," another number one hit. Smokey embarked on his own solo career and had a steady string of hits from 1973 through the late 1980s.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Got a Job - 1958

- Bad Girl - 1959

- It - 1959

by Ron and Bill - Way Over There - 1960

- Shop Around /

Who's Lovin You - 1961 - Ain't It, Baby - 1961

- Broken Hearted /

Mighty Good Lovin' - 1961 - Everybody's Gotta Pay Some Dues - 1961

- What's So Good About Good-by /

I've Been Good to You - 1962 - I'll Try Something New - 1962

- You've Really Got a Hold on Me - 1963

- A Love She Can Count On - 1963

- Mickey's Monkey - 1963

- I Gotta Dance to Keep From Crying - 1963

- (You Can't Let the Boy Overpower) The Man in You - 1964

- I Like it Like That - 1964

- That's What Love is Made Of - 1964

- Come On Do the Jerk - 1964

- Ooo Baby Baby - 1965

- The Tracks of My Tears - 1965

- My Girl Has Gone - 1965

- Going to a Go-Go /

Choosey Beggar - 1966 - Whole Lot of Shakin' in My Heart (Since I Met You) - 1966

- (Come 'Round Here) I'm the One You Need - 1966

- The Love I Saw in You Was Just a Mirage - 1967

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles /

Come Spy With Me - 1967

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - More Love - 1967

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - I Second That Emotion - 1967

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - If You Can Want - 1968

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Yester Love - 1968

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Special Occasion - 1968

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Baby, Baby Don't Cry - 1969

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Doggone Right - 1969

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Abraham, Martin and John - 1969

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Here I Go Again - 1969

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Point it Out - 1969

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles /

Darling Dear - 1970

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - The Tears of a Clown - 1970

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - I Don't Blame You at All - 1971

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - I Can't Stand to See You Cry - 1972

as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles - Do It Baby - 1974

- Love Machine - 1975