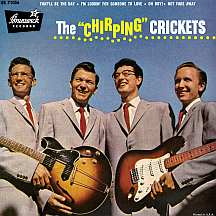

BUDDY HOLLY

AND THE CRICKETS

The tragedy of February 3, 1959 is remembered, honored and mourned by many, whether they heard about it at the time or in subsequent years when the anniversary came around, or through studying history and its prominent place as part of the lore of the rock and roll era. The deaths of J.P. Richardson, Ritchie Valens and Buddy Holly, their bodies found in a snowy field amid the wreckage of a plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa en route to a concert performance, is grievously stamped on the hearts of fans of the era's music. In 1971, Don McLean referred to it as 'the day the music died' in the lyrics of his renowned hit "American Pie" and for many the song represents the concept of a perceived death of rock and roll, however premature. In actuality, the music did not die that day, though there was certainly an aftershock that may have slowed it for a brief time. I never bought into the popular interpretation of McLean's song, seeing it as a coming-of-age story that included one 13-year-old paperboy's reaction to the 'bad news on the doorstep.' Being too young to have my own immediate reaction, I now consider it a setback in the development of the rock movement (made more distressing by further air disasters, auto accidents, overdoses and even a handful of murders yet to come). Bottom line: the music lived, and still does, though that isn't much consolation for the victims' loved ones and extended musical family.

Charles Hardin Holley, the youngest of Lawrence and Ella Holley's four children, was born in Lubbock, Texas in 1936 and became a music lover at an early age, his main fascination the clear channel radio stations he heard at night, coming from points north, south, east and west, bringing a variety of pop, country, jazz and rhythm and blues within reach of his ears. A yearning to perform inspired him to study guitar, banjo and mandolin and during high school, he and close friend Bob Montgomery started a band with Larry Welborn, a local kid who played bass. In 1953 they performed country and bluegrass songs on Sunday Party, broadcast on Lubbock's KDAV-AM 1590. Buddy's guitar playing took on an increasingly rhythmic style as R&B and rock music increased in popularity. They started referring to themselves as a "Western and Bop" act.

Up-and-coming rocker Elvis Presley spent a lot of time on the road in 1954 and '55 and played in Lubbock a few times; Buddy and Bob opened for him at the Cotton Club, a local dance hall. When the initially-percussionless Elvis showed up with a drummer, Buddy decided he wanted one too and convinced his friend Jerry Allison to join the group. They recorded some demo tapes at Buddy's house and later went to the Jim Beck Studio in Dallas and the Nesman Studio in Wichita Falls, seeking a more professional sound. Nashville-based agent Eddie Crandall helped get Holly a contract with Decca Records near the end of 1955 (just after Elvis had signed with RCA Victor). Decca was only interested in Buddy, though members of his band played on some recordings. Montgomery continued strictly as a songwriting partner. Buddy felt optimistic, figuring that if Bill Haley did so well with Decca, why couldn't he?

The first session took place in early 1956 at Bradley's Barn in Nashville with the studio's owner, Owen Bradley, producing. Larry and Jerry couldn't participate because they were still in high school, so Buddy brought along two other Lubbock-area friends, guitarist/fiddler Sonny Curtis and bassist Don Guess. His first single was "Blue Days-Black Nights" (written by KDAV deejay Ben Hall) backed with "Love Me" (penned by Buddy and Sue Parrish, an aspiring songwriter from Lubbock). Despite receiving airplay on a small number of stations, the single was not successful, though it was enough to get him booked on tours as an opener for Sonny James and Faron Young.

The experience at Bradley's Barn hadn't been to Buddy's liking and with another session scheduled several months out, he found the time to make a trip to Clovis, New Mexico (about a hundred miles west of Lubbock, just past the state border) to check out a place he'd been hearing about. Norman Petty had opened the Nor Va Jak studio in 1954 with the money he'd made from a top 30 hit with The Norman Petty Trio on "X" Records (a remake of Duke Ellington's "Mood Indigo"), which featured his wife, organist Vi Petty, and guitarist Jack Vaughan (the "Va" and "Jak" in Nor Va Jak). Unlike most studios, Norm charged by the song (not the hour), which appealed greatly to young musicians on a tight budget. Buddy figured it would be a cost-effective way to get in more practice time in a professional setting before his next Decca session.

Several good demonstration recordings were made in Clovis during the summer and spring of '56; Buddy's vocals took on more of a rockabilly sound thanks to Petty increasing the reverb and Sonny Curtis had begun to harness a little of the Scotty Moore magic that had made Elvis's Sun discs so special. In July, Holly, Guess, Curtis and Allison arrived in Nashville with more confidence; Buddy performed "Rock Around With Ollie Vee" with a purposely-stuttering vocal approach and cut loose on a remake of The Clovers' 1952 hit "Ting-A-Ling" while Decca execs, and producer Bradley, reacted with disdain for their amped-up rock sound. None of the songs they did were released (at least not right away) and Buddy was later told his three bandmates would not be welcome at the next session (in November), nor would there be any further need for him to play guitar. Sam Phillips-type visionaries they were not!

At that fateful fall session, "Modern Don Juan" was mastered using non-rocking pros Grady Martin (on guitar) and Boots Randolph (on sax); the track, devoid of any of Buddy's naturally-developed hiccups, was at best a passable effort that lacked the excitement of the summertime tunes. Decca head Paul Cohen thought he sounded terrible; Owen Bradley was less than thrilled with "That'll Be the Day," another song they recorded that the label decided not to release. The whole relationship was going downhill fast. At the end of his one-year contract, Decca booted Buddy from their roster. His career was over in just one year...or so it seemed...but the kid with the horn-rimmed glasses had come up with a different plan. He headed back to Clovis, where Norm Petty had been more positive about his talent...and more accommodating. Curtis and Guess decided to move on, though Buddy's school pal Jerry Allison stayed with him.

Then...another Buddy at the Nor Va Jak facility beat Lubbock's Buddy to the top of the charts! Happy, Texas native Buddy Knox's Clovis-recorded "Party Doll" secured Billboard's number one spot in March 1957, six months before Buddy Holly pulled off the same feat...with a track Bradley had told him was the worst song he'd ever heard! The idea for "That'll Be the Day" came from a line John Wayne repeated several times in The Searchers. Decca's flat-out rejection of the song didn't stop him from giving it another try. In February, Buddy, Larry, Jerry and South Gate, California-born guitarist Niki Sullivan recorded a second version in Clovis. They did dozens of takes in an attempt to get it perfect. Hoping to avoid any issues with first-version-owner Decca, it was credited to The Crickets, a group name Buddy and Jerry came up with.

The finished master was sent to Roulette (Knox's label) and Columbia (headed by the rock-resistant Mitch Miller), getting a thumbs-down on both counts. Petty got in touch with his publisher, Murray Deutch, who connected him with Coral Records, a subsidiary of Decca that had an entirely different staff. A&R head Bob Thiele liked the song but his bosses were less impressed, so he arranged to have it released on Brunswick (not adverse to signing black artists or rockers, the company basically had the lowest priority of Decca's labels). Buddy ended up signing two contracts: as a solo act with Coral and under an agreement with Brunswick that included the Crickets. The recordings henceforth were made with all four (Holly, Allison, Sullivan and newest member, bass player Joe Mauldin), regardless of how the releases were labeled. After all the problems with Decca, they were now tied to the company's two subsidiaries.

"That'll Be the Day" worked its way to number one in September 1957. When asked about it afterwards, Owen Bradley, who'd tried to steer Buddy in a country direction, admitted his misjudgement, calling his time as Holly's producer "...sort of a disaster." Over the next seven months, the group practically lived in Petty's studio, meticulously recording as many songs as possible for future use...and several of their greatest tracks came from this period. They also booked a show in Carlsbad, New Mexico, a spot popular artists seldom passed through, and blew the roof off the place with a rocking three hour show; it was a career high point, an adrenaline rush that made them feel like stardom was certainly within reach.

Buddy's first so-called solo single, featuring a double-tracked lead vocal, was "Words of Love," which he composed himself. It was released a month after the Crickets disc and failed to reach the charts (while a very good cover by The Diamonds pulled off the feat). As "That'll Be the Day" started making progress in August, Decca issued the previously-recorded demo of "That'll Be the Day" under the name Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes and flipped it with one of the best songs to come out of the Decca fiasco, "Rock Around With Ollie Vee." With the Brunswick version climbing the charts, they began touring the U.S. extensively, billed as two-acts-in-one, Buddy Holly and the Crickets, despite the separate single releases. In a few cities, the band was accidentally booked at venues that usually catered to black patrons. They easily won over the audiences each time, except in a few cases where local police stepped in and prevented them from appearing on the same bills as black artists due to one local ordinance or another. The tour continued nearly nonstop until the following spring, which included a trip to England during the later weeks.

Once the Crickets had broken through, the stage was set for Buddy's first "solo" hit; the original title of "Peggy Sue" was "Cindy Lou" after Jerry's niece. Experimenting with different arrangements, Buddy suggested Jerry play a paradiddle beat (rapid-fire: pudda-pudda-pudda-pudda-PUDDAH-PUDDAH-PUDDAH-PUDDAH...). The sound was attention-grabbing whenever it came on the radio and the drumming went well with Buddy's stuttering vocal approach. The single peaked at number three on Billboard in December '57 and number two on Cash Box in January '58. "Everyday" wasn't too shabby either, coming together more quickly than its A side; Buddy's vocals were on-point, Petty played celeste on the soft ballad and Jerry started slapping his knees...and that was it. A sweet knee-slapper and two-sided hit.

"Oh, Boy!" (written by another Lubbock-area musician, Sonny West) hit the streets immediately after "Peggy Sue." At one point in December, all three singles (two Crickets, one Holly) were in the Billboard top 40 simultaneously, just as the band made an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, bringing their starmaking rise to its apex; many fans who hadn't seen them yet realized the Crickets and Buddy Holly were one and the same. Just after 1958's New Year, "Oh, Boy!" joined "Peggy Sue" in the top ten (the Crickets' flip side, "Not Fade Away," would eventually gain classic status after The Rolling Stones kicked off their American string of hits with a rad remake of the song in '64).

It was a good thing Buddy and his bandmates had gotten all those recordings finished during the months-long waiting period, so material would be available to release while on the road. But the labels wanted more, so they had to arrange for quick sessions in various studios and the results obtained under pressure were surprisingly good. Petty set up a date at an Air Force base in Oklahoma City; the master of the Crickets' next hit, "Maybe Baby" (inspired by a phrase Buddy's mother often used) resulted. Holly's next single for Coral was "Listen to Me," oddly another no-show on the U.S. charts, though it went top 20 in the U.K. once Hollymania broke out during the British leg of the tour in March.

"Rave On" ('...it's a crazy feelin'!') was Holly's next solo disc, written and released on Atlantic by Sonny West in early '58 and recorded by Buddy in New York soon afterwards; it reached the top 40 in June. "Think it Over" (top 30 for the Crickets in August) and its flip, "Fool's Paradise," were squeezed in between the last U.S. date and their departure for the U.K. tour. Decca dusted off "Ting-A-Ling" and pressed it as another Holly/Three Tunes single before giving up on milking the band's fortunes. A large-scale session had taken place in June at the Pythian temple in Manhattan's Lincoln Suare neighborhood with an orchestra under the direction of Dick Jacobs that included saxophonist Sam "The Man" Taylor and a female gospel quartet. "Early in the Morning," a cover of a song recorded by Bobby Darin under the name The Ding-Dongs on Brunswick and later issued as The Rinky-Dinks on Atco, Holly's version on Coral was rush-released to compete with Darin's. Both coexisted in the top 40 in August alongside the Crickets' "Think" tune.

Next came a weird song by Ivan...Jerry Allison's middle name. Originally by Australian rocker Johnny O'Keefe and his band The Dee Jays, Buddy's crew had heard "Real Wild Child" while touring down under in February. Jerry's oddly nerdy vocals obscured the fact it was by Holly and the Crickets, yet it spent several weeks on the singles charts (there was one follow-up by Ivan: "That'll Be Alright"...another O'Keefe song). It's may surprise some that the Ivan record spent time on best seller lists while the Crickets single "It's So Easy!," considered one of the act's greatest songs today, failed to make a dent. Tommy Allsup played guitar on the track and was soon slotted as a replacement for the daparting Sonny Curtis. Tommy was also featured on "Heartbeat," recorded in Clovis that summer and backed by the outstanding "Well...All Right," a Bob Montgomery song the band had thrown together while on tour.

Buddy had spotted Maria Elena Santiago in June, working the front desk of Murray Deutch's office at Peer-Southern Music. He asked her out, she agreed, he proposed the same night, they were married in August in Lubbock, then returned to New York (Maria Elena's home since childhood) and rented an apartment in Greenwich Village. Maria saw firsthand how ambitious Buddy was; he wanted to experience every facet of the music business over the course of the long career he envisioned. He also wanted to take control of his own finances, due to the certainty he and the band hadn't received fair compensation from Petty. Ever since his tour of Britain and the experience with "Early in the Morning," he'd been thinking about making a change. The move to N.Y. fit with his plan to work with Dick Jacobs. Coral brass had suggested he break away from rock and roll in favor of a "pop" sound and even Petty agreed. Buddy didn't plan to completely abandon rock and roll, but had a desire to experiment with different styles that couldn't be denied.

On October 28, 1958, the group performed on American Bandstand, which turned out to be their final television appearance. Soon afterwards, the Crickets broke up; Allison and Mauldin would continue as Crickets and Buddy would venture forth as a New York-based solo act. His next single, one of the songs he worked on with Jacobs after moving to New York, had a string-arranged pop sound. Penned by Paul Anka, it was his first stereo recording (though only issued at the time in mono). Flip side "Raining in My Heart" (composed by Boudleaux and Felice Bryant of Everly Brothers fame) had the same kind of string arrangement. Coral put it out just after the New Year.

In late January, Buddy headed out on a three-week tour of the midwest called the "Winter Dance Party" with Ritchie Valens, The Big Bopper, Dion and the Belmonts and Frankie Sardo. One bus they were traveling in had poor heating and another bus kept breaking down, partly due to hazardous road conditions as frequent snowstorms blanketed the upper midwest states they were traveling through. The backing band he'd hired as the Crickets consisted of guitarist Allsup, drummer Charlie Bunch and Lubbock-area deejay, guitarist and singer Waylon Jennings (who'd been working on some recordings with Buddy in Clovis). Right before a show at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy got fed up with the inconvenience and chartered a four-seat private plane to take the group (minus drummer Bunch) to the next stop in Moorhead, Minnesota as soon as their time on stage was finished.

Valens and J.P. "Big Bopper" Richardson talked Allsup and Jennings into giving up their seats (or, by some accounts, flipped coins for the privilege); they headed out around 1AM on February 3 with pilot Roger Peterson. It wasn't until after dawn that the Hector Airport in Fargo, North Dakota near Moorhead reported the plane hadn't arrived. Less than ten miles from where they'd departed, the wrecked plane and all four bodies were found in a cornfield. Former Crickets members and many music business friends attended Holly's funeral on Saturday, February 7 in Lubbock. His pregnant wife Maria Elena wasn't able to attend (adding to the tragedy, she suffered a miscarriage hours before the service).

The surviving Crickets were in no state of mind perform that night, so when Fargo radio station KFGO reported the news of the tragedy on-air, it was mentioned that the show's promoters were looking to hire acts to cover the Crickets' slot. 15-year-old Bobby Vee, who was in an unnamed band with his older brother Bill and two other friends, went to the audition and landed a spot. Calling themselves The Shadows, they performed as an opening act yet didn't do any Holly/Crickets songs. By chance, doors opened for singer Vee after a promoter caught his Hollyesque performance and before long he and the Shadows had a record out on the local Soma label, "Suzie Baby." Liberty Records of Los Angeles signed Vee and he was a major star throughout the '60s, his career having started on the same day Buddy Holly's life ended.

"It Doesn't Matter Anymore" suddenly felt mournfully prophetic. It quickly reached the top 20 in the U.S. and became Buddy's only number one hit in Great Britain. "Midnight Shift," recorded in '56 at the very first Nashville session, was released in the U.K. and became a hit. Many of those demo tapes, including some made in Wichita Falls, others he'd taped in his family's garage and still others recorded in his New York apartment not long before his death, came into his widow's possession, which she made available to Dick Jacobs and the staff at Coral Records. They hired seasoned musicians to supply instrumental backing and some of the results appeared on 45s, including "Peggy Sue Got Married" and "True Love Ways" (the latter dedicated by Buddy to his wife). In 1962, Norman Petty gained control of the tapes and continued the remastering process of the songs that were still contracted for release by Coral. Many were voice-and-guitar demos enhanced by Petty with instrumentation by The Fireballs, a popular group that recorded at the Clovis studio for the better part of a decade. Other producers worked with some of the demos in similar fashion and the majority of those were released throughout the 1960s.

The Crickets remained together for years to come. Earl Sinks, a singer from the same part of Texas who'd done some recording at Petty's studio, took over Buddy's spot as lead singer. In 1960 he was briefly replaced by Earl Box of Lubbock (who, in a bizarre "history-repeats-itself" twist, died in the crash of a chartered plane in 1964). Other members came and went, including Glen D. Hardin (a songwriter from Wellington, Texas and, later, an accomplished session musician) and Texan Jerry Naylor (whose solo career as a country singer kept him busy throughout the '70s and '80s). Guitarist Sonny Curtis rejoined the group after serving in the military, remaining with them for decades while enjoying notable success as a songwriter. Drummer Jerry Allison, one of Holly's best friends since childhood, was the longest-tenured Cricket.

In England, Holly's recordings and those made by the later lineup of Crickets were top sellers over the next few years. A few of Buddy's singles reached minor positions in the U.S. but were very big in the U.K.; "Bo Diddley," "Brown-Eyed Handsome Man" (originally by Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry, respectively) and Holly-Montgomery composition "Wishing" were all top ten hits. After a number of Brunswick and Coral releases, the Crickets signed with Liberty Records. In Britain they reached the top ten in 1962 with the Gerry Goffin-Carole King song "Don't Ever Change" and the same year reached the U.S. chart with "Someday (When I'm Gone From You)" in a collaboration with Bobby Vee. One final single came ten years after that fateful night: "Love is Strange" by Mickey and Sylvia, a favorite of Buddy's that inspired "Words of Love," had strings added to his demo recording. This version made a brief appearance on the national charts in the spring of 1969.

Many British and American stars have recorded successful Holly remakes, including the Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Peter and Gordon, The Bobby Fuller Four and Linda Ronstadt. Tommy Roe honored Buddy in his own way by fashioning his hit "Sheila" after "Peggy Sue." In 1973, Norman Petty sold Holly's catalog to publically-acknowledged fan Paul McCartney, who has actively promoted the music so that it will continue to resonate with coming generations. Maria Elena, who as Holly's widow owns all intellectual property concerning him, has also participated in efforts to promote the music and memory of her late husband. His legend still lives decades later through films, a stage play and the steady flow of songs that are heard on many platforms. Buddy Holly and the Crickets remain a vibrant part of pop culture.

And Maria Elena Santiago Holly has admitted in interviews that the "love at first sight" she and Buddy both felt that evening in June 1958 has been a lasting one, despite the fact they were only together for about seven whirlwind months. Her love for him has persistently, actively endured her entire life.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Blue Days-Black Nights - 1956

as Buddy Holly - Modern Don Juan - 1956

as Buddy Holly - That'll Be the Day

as the Crickets / - I'm Lookin' for Someone to Love - 1957

as the Crickets - Words of Love - 1957

as Buddy Holly - Rock Around With Ollie Vee

as Buddy Holly / - That'll Be the Day - 1957

as Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes - Peggy Sue

as Buddy Holly / - Everyday - 1957

as Buddy Holly - Oh, Boy!

as the Crickets / - Not Fade Away - 1957

as the Crickets - Love Me - 1958

as Buddy Holly - Maybe Baby - 1958

as the Crickets - Listen to Me - 1958

as Buddy Holly - Rave On - 1958

as Buddy Holly - Think it Over

as the Crickets / - Fool's Paradise - 1958

as the Crickets - Ting-A-Ling - 1958

as Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes - Early in the Morning - 1958

as Buddy Holly - Real Wild Child - 1958

by Ivan - It's So Easy! - 1958

as the Crickets - Heartbeat

as Buddy Holly / - Well...Alright - 1958

as Buddy Holly - It Doesn't Matter Anymore

as Buddy Holly / - Raining in My Heart - 1959

as Buddy Holly - Love's Made a Fool of You - 1959

by the Crickets - Midnight Shift - 1959

as Buddy Holly - Peggy Sue Got Married - 1959

by Buddy Holly - True Love Ways - 1960

by Buddy Holly - Don't Ever Change - 1962

by the Crickets - Someday (When I'm Gone From You) - 1962

by Bobby Vee and the Crickets - Reminiscing - 1962

by Buddy Holly - Bo Diddley - 1963

by Buddy Holly - Brown-Eyed Handsome Man - 1963

by Buddy Holly / - Wishing - 1963

by Buddy Holly - What to Do - 1965

by Buddy Holly - Love is Strange - 1969

by Buddy Holly