FATS DOMINO

December 10, 1949: Bandleader-producer Dave Bartholomew and a group of New Orleans' finest, most street-smart musicians assembled at Cosimo Matassa's studio on Rampart Street for the first recording session featuring a young piano-pounder named Antoine Domino. They couldn't have known it at the time, but it was one of music history's cornerstone moments, a recording session the results of which heavily influenced the direction music would take over the decade that followed. The studio had been built a few years earlier as a result of Matassa's love of blues and rhythmic music and desire to do more than simply work at his Italian family's grocery store located adjacent to the space that became the J&M studio, which Cosimo later named after himself. If that seems a bit self-centered, it was entirely justified; for many years, Cosimo did all the recording and engineering as the studio became the unassuming yet grand central hub of music production in the south. Bartholomew was convinced early of Matassa's passion and the sonically ideal conditions the studio presented. He never considered recording Domino, his promising discovery, anywhere else.

Bartholomew was born in 1920 in Edgard, Louisiana, about 50 miles to the east of New Orleans on the Mississippi River. He began practicing trumpet around age ten with instruction from Peter Davis, who'd taught Louis Armstrong some two decades earlier; within a couple of years Dave would occasionally join his father, a tuba player, in local bands, sometimes performing on riverboats. Before long people were calling him "Little Davey" Bartholomew. He formed his own band shortly after the end of World War II, working clubs in and around the Big Easy. A series of guest shots on the WJMR radio show hosted by Vernon "Dr. Daddy O" Winslow ("The First Colored Disc Jockey in New Orleans") led to a contract with DeLuxe Records, where he worked with Roy Brown and recorded his own sides.

Imperial Records owner Lew Chudd, in New Orleans during the fall of 1949 scouting for acts to sign, caught Bartholomew's set in a local nightclub and made him an offer. As he was already a recording act for DeLuxe, he signed with Chudd as a producer and A&R man. He wasted no time in bringing promising acts to the roster of the two-year-old label, starting with Mary Jewel King in late November; she had made some recordings for DeLuxe but none were released. Her 1950 hit as Jewel King, "3 x 7 = 21" ('I'm going out there and have myself some fun!'), came out of that first session. Dave had heard the buzz on Fats Domino, who'd been playing with Billy Diamond's band at the Hideaway Club on Desire Street, so he took Chudd down to check out the show in this place that lived up to its name, hidden from plain view across the tracks at the end of a path (the sound of the blasting music filling the air well before the juke joint itself could be seen). Domino's indefatigable piano playing frequently raised the crowd to excitable levels and the two knew right away they wanted him for Imperial.

Antoine Domino was a New Orleans native fiercely loyal to the city, particularly the Lower Ninth Ward where he'd lived since his birth in 1928. His brother-in-law, Harrison Verret, was so thorough a mentor and the young Antoine so rapid a learner that he became a highly skilled piano player in an amazingly short period of time. He wasn't much more than ten when he started performing in and around the French Quarter, right down the street from the house he grew up in; the gig with Billy Diamond, who suggested the hefty teenager call himself "Fats," came in 1946. Patterning himself after local blues pianist Isidore "Tuts" Washington (who'd backed up Domino contemporary Smiley Lewis), Antoine was so loyal to his home town that at first he refused (or wasn't able) to see the "big picture." The worldwide stardom he later achieved was beyond the limits of his imagination. New Orleans was his world, making a living there as a musician his primary goal. He married Rose Mary Hall and settled down to raise a family in the old neighborhood, with no plans to live anywhere else.

When Fats Domino signed with Imperial in late '49, Verret advised him to insist on royalties for his work instead of regular pay (a more common practice with small labels in those days); Chudd went along with the deal and it had a positive effect on the singer's future earnings, to say the least. "Detroit City Blues" christened what became the formidable songwriting team of Domino and Bartholomew. Intended as the A side of the first Fats single, it was eclipsed by its flip, a heavyhanded piano piece with simple lyrics based on a thing called "The Junker's Blues": 'They call me a junker, 'cause I'm loaded all the time...' Lyrics were adjusted accordingly: 'They call, they call me the fat man...'cause I weigh two hundred pounds!' (last time I checked, a two hundred pound man isn't exactly overweight unless he's five-foot-five...which, as it turns out, is Domino's height). A wailing 'Wah-wah-wah-wah...' added to the force of "The Fat Man," which hit the rhythm and blues charts in February 1950 (after local disc jockeys voiced their preference for it over the "Detroit" side), a top ten hit and eventual million seller. Jewel King's record was a hit within a few weeks and Bartholomew, on DeLuxe, made the R&B charts around that time with "Country Girl," his only national hit (as a recording act, that is); Chudd locked him up with an exclusive Imperial contract shortly afterward.

Bartholomew developed a reputation as a taskmaster, seeking perfection in Cosimo's less-than-perfect surroundings (where imperfect recordings were often preferable); some referred to Dave as a "slave driver." He considered "The Fat Man" and "Detroit City Blues" primitive recordings (which to some degree they were - that was part of their magic) and had misgivings about the record's release...until it became a hit, of course. Still, he had the best musicians in the area working on his sessions: sax men Alvin "Red" Tyler, Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty, guitarist Ernest McLean, bassist Frank Fields, drummer Earl Palmer, Domino on piano and several others; Dave also played trumpet on some recordings. The next two singles, despite top-notch musicianship, failed to catch on. Next came "Hey! La Bas Boogie," a hot number with a fast-fingered keyboard workout and sizzling sax break, which went over well locally but didn't develop into a hit. Then came "Every Night About This Time" ('...I go to sleep to keep from cryin'...'), a slower-paced blues that put him back in the R&B top ten near the end of the year.

Around this time, Dave Bartholomew left Imperial because of a disagreement over the money Chudd was paying (or not paying) him. Fats began working with Al Young, but 1951 was a tough year; only one song, "Rockin' Chair," hit the charts, the final week in December. Fats did some touring with a new band that featured Billy Diamond on bass, saxophonist Wendell Duconge, guitarist Walter "Papoose" Nelson, drummer Cornelius "Teenoo" Coleman and brother-in-law Verret on guitar. Bartholomew, meanwhile, produced sessions for Specialty (Lloyd Price), Aladdin (Shirley and Lee) and other labels.

Domino scored his biggest hit yet in the spring of 1952, "Goin' Home," his one major collaboration with Al Young. The record topped the R&B charts in June 1952, knocked off after one week by Price's "Lawdy Miss Clawdy," one of the all time New Orleans smashes, written and produced by Bartholomew, who'd convinced Fats to play piano at the session. After that record's success, Lew Chudd made amends with Bartholomew and the team of Fats and Dave reunited after almost two years apart. The first of their phase two singles, "Going to the River," had competition from Chuck Willis's cover version on Okeh; both were top ten R&B hits, with the Domino version spending the entire month of June '53 at number two. "Please Don't Leave Me," with a 'Woo-woo-woo-woo...' reminiscent of "The Fat Man," came on its heels and was almost as big.

"Rose Mary" was next, a tribute to his wife (and eventual mother of four boys and four girls, all taking after their dad with names that begin with "A") which Fats insisted was the only one of the many "girl title" songs he recorded with a real person in mind. By the end of 1953 Chudd, anxious to hang on to his biggest record seller (two million since 1950 and counting, impressive in the rhythm and blues market of the early '50s), made Domino an unheard-of offer: an iron-clad nine year contract extension. Hits kept coming steadily, then in 1955 the other nine-tenths of the world found out about New Orleans' most popular personality.

'You made me cry...when you said goodbye...ain't that a shame!' kicked off the dynamic performance (oddly titled "Ain't it a Shame" despite the lyrical difference) that raised Domino's profile and brought him closer to superstardom; timed perfectly to the rise of rock and roll music and pop radio's growing acceptance of rhythm and blues, it spent most of the summer of 1955 at the top of the R&B charts and had a strong run on the pop charts as well. As it turns out, Pat Boone overshadowed the original with a better-selling pop cover that was appealing in its own vastly different way, but Domino's crossover success opened the door for more. After the R&B hits "All By Myself" and "Poor Me" (the latter very similar to "Ain't"), "Bo Weevil" followed a similar pattern of popularity to that of the groundbreaking hit, with a perky cover by Teresa Brewer grabbing the glory (though Domino's version was a top 40 hit). The next single, "I'm in Love Again," battled a cover by The Fontane Sisters and handily won, giving the Fat Man his first bona fide top ten pop hit (and third number one R&B seller). After that, pop cover acts seemed to follow a hands-off policy; when a Fats Domino song became a hit, it was by Fats Domino...and for a long time to come, every single release was a hit.

'I found my thrill...' began the song that made Fats Domino a household name. "Blueberry Hill," written by Al Lewis, Larry Stock and Vincent Rose, had been a hit in 1940 for Glenn Miller (with singer Ray Eberle) and was recorded by others including Louis Armstrong (whose 1949 version was revived right after Domino brought it to everyone's attention). A strange choice considering everything to that point had been an original composition, it became, and has remained, Domino's signature song after spending most of the fall of '56 and early '57 at the top of the R&B charts and in the pop top ten. The song's flip, "Honey Chile," was the intended A side (it became a solid R&B hit); when Domino made his first film appearance in Shake, Rattle and Rock!, it was this side he performed (in addition to "I'm Love Again" and "Ain't it a Shame") in place of what certainly would have been the show-stopping number.

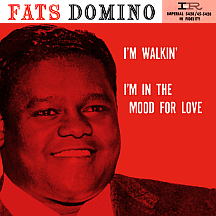

Going straight back to the winning Domino-Bartholomew formula, Fats revived "Blue Monday" (recorded a couple of years earlier by Smiley Lewis), an automatic top ten pop/number one R&B hit based purely on its relatability to the working man. He performed the song onscreen in The Girl Can't Help It, starring the hard-to-miss Jayne Mansfield (theme song provided by Little Richard), in living color this time around. The fast-paced "I'm Walkin'" sent him straight to the hit levels of the previous three singles while battling a rockin' cover on Verve by Ricky Nelson (the one person who obviously didn't get the "hands off" memo!), the very first record by the 17-year-old TV star and future Imperial Records artist. "Valley of Tears", "It's You I Love" and "Wait and See" were major components of a hit-filled '57 for the Fat Man. He was one of the hottest artists in rock and roll, but such a designation confused him. He claimed it was just the same rhythm and blues he'd been playing for several years; the difference was that by the mid-'50s, teenagers in all walks of life were discovering R&B and embracing it.

Domino and Bartholomew (together, but perhaps not as much when working apart) possessed rare songwriting skills. When it came to the difficult task of writing brilliantly infectious songs, they had the knack. Year after year, song after song, the two came up with inspired melodies and ingeniously simple lyrics, a task that's harder than it might seem to one who hasn't tried it. Throughout the 20th century, only a handful have achieved anything comparable for long periods of time. The masters of Tin Pan Alley, many of the Brill Building songwriters, Chuck Berry, Leiber and Stoller, Smokey Robinson, Lennon and McCartney in their early years, a few others, perhaps; all of them possessed that elusive flair when it came to composing pop songs. Fats and Dave belong on that short list. Besides Domino's own string of hits, they supplied songs for some of New Orleans' top-rate artists including Bartholomew himself (the joyously gospel-flavored "Jump Children"), Roy Brown ("Let the Four Winds Blow"), Chris Kenner ("Sick and Tired") and Smiley Lewis ("I Hear You Knocking," cowritten with Pearl King, a hit for Lewis as well as pop singer and TV star Gale Storm).

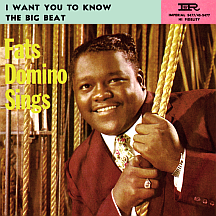

Around 1958, engineers at Imperial Records in Los Angeles began speeding up some of Domino's masters ever-so-slightly in an attempt to give his songs a "younger" sound (the singer, not exactly a senior citizen, had just turned 30). Fats wasn't happy when he heard the results on the radio, but the practice continued despite his protests. Fats had become a headliner on the the rock and roll package shows of the day; Alan Freed, in particular, booked him for big events in New York City. His many television appearances included the high-rated Steve Allen and Perry Como variety shows and Dick Clark's hotter-than-hot American Bandstand. Two more movies showcased the up-close-and-personal talent of Fats Domino: Jamboree (in '57) and The Big Beat, featuring his hit '58 title song.

As prolific as they were as songwriters, even Fats and Dave had their creative dry spells. Sometimes a decision would be made to redo a song they'd given to another artist. "Sick and Tired" was one example; a breakthrough hit for Chris Kenner (signed to Imperial at the time) in the summer of '57, it was tackled by Fats several months later and became a top 40 hit in the spring of '58. The hits continued nonstop (most of them two-sided, resulting in eight or nine songs appearing on the national charts in any given year), highlighted by uptempo pleasures "Whole Lotta Lovin'," "I'm Ready" and "I'm Gonna Be a Wheel Someday" (which varied from the norm, as it was written by Roy Hayes of Baton Rouge), plus the number one R&B smash "I Want to Walk You Home" and decade-closing chartbuster "Be My Guest."

Momentum didn't slow a bit as Fats fell into the 1960s; ten songs charted that first year! "Walking to New Orleans" reminded listeners of the city their beloved Fat Man called home. The song was written by Robert Guidry (who recorded for Chess as Bobby Charles) after Fats invited him to the Crescent City for a visit; Bobby said he had no money and Fats jokingly replied, "Why don't you walk to New Orleans?" A string section, something not previously used, added to the song's sentimental flavor. After it went top ten in August, Domino began using more string arrangements, as well as background singers, on his recordings, including the next hit, "Three Nights a Week." Other highlights of the early '60s include the Domino-Bartholomew song "My Girl Josephine," the bluesy "What a Price" (written by Domino with Jack Jessup and Peewee Maddux), gospel-tinged "Fell in Love on Monday," midtempo ballad "It Keeps Rainin'" (a collaboration with Bobby Charles) and "Let the Four Winds Blow" (an original that was previously a top 40 hit for Roy Brown in '57). Country music adaptations were popular also; Hank Williams tunes "Jambalaya (On the Bayou)" and "You Win Again" were solid hits for Fats in early '62.

At the end of his long, hit-filled contract with Imperial, Domino found it impossible to resist a tempting offer from ABC-Paramount Records, the label that had sent the career of Ray Charles into the stratosphere a few years earlier. He left Imperial in late 1962 after more than 13 years; Ricky (now going by Rick) Nelson also severed ties and went to Decca at about the same time. Having lost his two biggest acts, Lew Chudd decided to call it a day and, in the summer of 1963, sold the company to Liberty Records. Chudd retained his association with Liberty for a time and even found a position in Los Angeles for Dave, who'd stopped working with Fats when he signed with ABC. Bartholomew had no desire to leave New Orleans and declined the offer.

Domino began recording in Nashville with producer Felton Jarvis and arranger Bill Justis, where he had less to say about the direction he wanted his music to take. Some of the ABC recordings retained the texture of the Cosimo masters while others had a straight country feel or were slickly produced pop efforts set against an overbearing choral backdrop. His two biggest hits for the new label were the self-penned, uptempo "There Goes (My Heart Again)" in the spring of '63 and "Red Sails in the Sunset," the Jimmy Kennedy-Hugh Williams classic dating to 1935; the latter became his only top 40 hit on ABC-Paramount in the fall. Other worthy singles from '63 and '64 (low charters all) include Don Gibson's "Who Cares" (stylistically a good fit) and Domino original "Lazy Lady." His time with ABC lasted just two years (Nelson had better luck at Decca), then he made records for Mercury and Bartholomew's homegrown Broadmoor label (named after the Broadmoor neighborhood in New Orleans).

In 1968 he joined the roster of Reprise Records, briefly reaching the pop charts in September 1968 with "Lady Madonna," the Beatles hit from earlier in the year that Paul McCartney admitted was patterned after Domino's singing style; produced by Richard Perry, it was strikingly similar to the Beatles' recording. With record sales at a near standstill, Domino spent most of his time on the road and appeared in Las Vegas for several months out of each year throughout the coming decade. In 1980 he appeared in Any Which Way You Can starring Clint Eastwood, performing "Whiskey Heaven" in a nightclub setting. Written by Cliff Crofford, John Durrill and Snuff Garrett (and produced by the seasoned Garrett), the song was released on Viva Records (a Warner Bros. label) and put Fats back into the public eye, and onto the country charts, in 1980.

Sometime in the early '80s, Fats Domino came to a decision similar to the one his longtime friend, Dave Bartholomew, had made years earlier...he no longer had a desire to leave his beloved New Orleans. Previous tours across America and in foreign countries had created a dilemma where food was concerned, as his preferred diet of Cajun cuisine wasn't always available. So after that he stayed close to his home in the city's Ninth Ward, seldom leaving southern Louisiana. He and his family settled into a happy routine in the city they loved; Domino frequently performed concerts in and around New Orleans. His family-, food- and music-oriented life was exactly as he wanted it to be.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the area in August 2005, that routine abruptly and shockingly came to a halt. Domino's house was flooded. Most of his lifelong possessions (including family artifacts and memorabilia from his heyday in the music business) were destroyed. His wife Rose Mary had been ill and was unable to leave; he chose to stay with her, as did one of their daughters. Friends and family suddenly lost contact with them. News reporters speculated on Domino's death. But the family survived and, after a few days of uncertainty, a rescue team took them to safety in a Coast Guard helicopter. "We lost everything," according to Fats. Everything, that is, but their lives.

Fats and his wife relocated to Harvey, Louisiana, on the south side of the stretch of Mississippi River that runs through New Orleans. Their house was eventually repaired and they moved back in. Several years earlier, in 1998, Domino had been the recipient of the National Medal of Arts, presented to him by President Bill Clinton, but it had been lost along with everything else. After Katrina, Clinton's successor, George W. Bush, traveled to New Orleans and personally replaced the medal. One award bestowed upon him by two U.S. presidents, a fitting tribute to "The Fat Man," a true national treasure.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- The Fat Man - 1950

- Hey! La Bas Boogie - 1950

- Every Night About This Time - 1950

- Rockin' Chair - 1951

- Goin' Home - 1952

- How Long - 1952

- Going to the River - 1953

- Please Don't Leave Me - 1953

- Rose Mary - 1953

- Something's Wrong - 1954

- You Done Me Wrong - 1954

- Don't You Know - 1955

- Ain't it a Shame - 1955

- All By Myself - 1955

- Poor Me - 1955

- Bo Weevil /

Don't Blame it on Me - 1956 - I'm in Love Again /

My Blue Heaven - 1956 - When My Dreamboat Comes Home /

So-Long - 1956 - Blueberry Hill /

Honey Chile - 1956 - Blue Monday /

What's the Reason I'm Not Pleasing You - 1957 - I'm Walkin' - 1957

- The Rooster Song - 1957

- Valley of Tears /

It's You I Love - 1957 - When I See You /

What Will I Tell My Heart - 1957 - Wait and See /

I Still Love You - 1957 - The Big Beat /

I Want You to Know - 1958 - Yes, My Darling - 1958

- Sick and Tired /

No, No - 1958 - Little Mary - 1958

- Young School Girl - 1958

- Whole Lotta Loving - 1958

- Telling Lies /

When the Saints Go Marching In - 1959 - I'm Ready /

Margie - 1959 - I'm Gonna Be a Wheel Some Day /

I Want to Walk You Home - 1959 - Be My Guest /

I've Been Around - 1959 - Country Boy - 1960

- Tell Me That You Love Me - 1960

- Walking to New Orleans /

Don't Come Knockin' - 1960 - Three Nights a Week /

Put Your Arms Around Me Honey - 1960 - My Girl Josephine /

Natural Born Lover - 1960 - What a Price /

Ain't That Just Like a Woman - 1961 - Fell in Love on Monday /

Shu Rah - 1961 - It Keeps Rainin' - 1961

- Let the Four Winds Blow - 1961

- What a Party - 1961

- Jambalaya (On the Bayou) /

I Hear You Knocking - 1961 - You Win Again - 1962

- My Real Name /

My Heart is Bleeding - 1962 - Nothing New (Same Old Thing) /

Dance With Mr. Domino - 1962 - Did You Ever See a Dream Walking /

Stop the Clock - 1962 - There Goes (My Heart Again) - 1963

- Red Sails in the Sunset - 1963

- Who Cares - 1964

- Lazy Lady - 1964

- Sally Was a Good Old Girl - 1964

- Lady Madonna - 1968

- Whiskey Heaven - 1980